Общий формат инструкции if

Как и в большинстве других языков программирования в Python присутствует условная инструкция

if, которая в общем случае имеет следующий формат записи:

if <Условие №1>:

<Блок инструкций №1>

elif <Условие №2>:

<Блок инструкций №2>

...

else:

<Запасной блок инструкций>

Если первое условие истинно (результатом вычислений будет True), то выполняется первый блок инструкций. Если первое условие ложно

(результатом вычислений будет False), то проверяются по-очереди все условия необязательных блоков elif и, если найдется

истинное условие, то выполняется соответствующий этому условию блок инструкций. Если все дополнительные условия окажутся ложными, выполнится запасной блок инструкций

else. Обязательным является только блок инструкций if, остальные блоки могут быть опущены. При этом разрешается

использовать любое количество блоков elif, но только один блок else.

Простейшая форма инструкции if

Давайте для наглядности начнем с простейшей условной инструкции. Она содержит только основную часть if, в которой вычисляется значение единственного

условного выражения и по результатам вычисления принимается решение – если конечный результат имеет значение True, интерпретатор выполняет указанный

фрагмент кода, а если конечный результат имеет значение False, интерпретатор пропускает данный фрагмент кода и начинает выполнять инструкцию, следующую за

текущей условной инструкцией (см. пример №1).

# Определяем польз. функцию.

def my_div(x, y):

# Осуществляем проверку условного выражения.

if y == 0:

# Выходим из функции и возвращаем None.

return None

# Возвращаем частное.

return x/y

# Вызываем функцию и публикуем результаты.

print(my_div(2, 4))

print(my_div(2, 0))0.5

None

Пример №1. Условная инструкция if и ее синтаксис.

Отметим, что в теле инструкции if разрешается использовать как другие вложенные инструкции if, так и вложенные

управляющие конструкции других видов, например, циклов или обработчиков ошибок, что значительно повышает возможности организации условного выполнения различных частей программы.

Управляющая конструкция if/else

Если в зависимости от результата проверки условного выражения нужно сделать выбор и выполнить только один из двух допустимых наборов инструкций, инструкция if

может быть расширена при помощи ключевого слова else, которое в случае, когда значение условия равно False, позволяет

выполнить альтернативный набор инструкций (см. пример №2).

# Определяем польз. функцию.

def my_func(x, y):

# Проверим равенство чисел.

if x == y:

print(x, 'равно', y, end='nn')

else:

print(x, 'не равно', y,)

# Вызываем функцию.

my_func(1.34, 1.43)

my_func(3, 3.0)1.34 не равно 1.43

3 равно 3

Пример №2. Расширение инструкции if за счет ключевого слова else.

Обратите внимание, что в нашем примере ложный результат имеет ценность для программы и не должен быть потерян. Поэтому для его обработки мы и добавили в условную инструкцию блок

else.

Ключевое слово elif

Когда требуется выполнить выбор не из двух, а из нескольких подходящих вариантов, инструкция if может быть расширена при помощи требуемого количества

ключевых слов elif, которые по сути служат для объединения двух соседних инструкций if

(см. пример №3).

# Определяем польз. функцию.

def my_price(f):

# Осуществляем проверку условных выражений.

if f == 'яблоки':

m = '1.9 руб/кг.'

elif f == 'апельсины':

m = '3.4 руб/кг.'

elif f == 'бананы':

m = '2.5 руб/кг.'

elif f == 'груши':

m = '2.8 руб/кг.'

else:

m = 'Нет в продаже!'

# Возвращаем результат.

return m

# Вызываем функцию и публикуем результаты.

print(my_price('апельсины'))

print(my_price('груши'))

print(my_price('мандарины'))3.4 руб/кг.

2.8 руб/кг.

Нет в продаже!

Пример №3. Расширение инструкции if за счет ключевых слов elif.

Как видим, при использовании ключевых слов elif выполнение альтернативного блока инструкций происходит лишь тогда, когда соответствующее блоку условие

имеет значение True, а условные выражения всех предыдущих блоков в результате вычислений дают False. В случае

отсутствия совпадений, выполняется набор инструкций дополнительного блока else.

Здесь будет уместным заметить, что в Python отсутствует инструкция switch, которая может быть вам знакома по

другим языкам программирования (например, PHP). Ее роль берет на себя конструкция if/elif/else, а также ряд

дополнительных приемов программирования, иммитирующих поведение этой инструкции.

Трехместное выражение if/else

Как и в случае с инструкцией присваивания, использовать условные инструкции в выражениях запрещается. Но иногда ситуации бывают настолько простые, что использование многострочных

условных инструкций становится нецелесообразным. Именно по этим причинам в Python была введена специальная конструкция, называемая

трехместным выражением if/else или тернарным оператором if/else, которая может использоваться непосредственно в

выражениях (см. пример №4).

# Инициализируем переменную.

x = 5

# Составляем условие.

if x == 0:

s = False

else:

s = True

# Выводим результат.

print(s)

# Используем выражение if/else.

s = True if x != 0 else False

# Получим тот же результат.

print(s)True

True

Пример №4. Использование трехместного выражения if/else (часть 1).

Таким образом, трехместное выражение if/else дает тот же результат, что и предыдущая четырехстрочная инструкция if,

но выглядит выражение проще. В общем виде его можно представить как A = Y if X else Z. Здесь, как и в предыдущей инструкции, интерпретатор обрабатывает

выражение Y, только если условие X имеет истинное значение, а выражение Z обрабатывается,

только если условие X имеет ложное значение. То есть вычисления здесь также выполняются по сокращенной схеме (см. пример №5).

# Инициализируем переменные.

x, y = 0, 3

res = True if x > y else False

# Выведет False.

print(res)

res = y/x if x != 0 else 'Division by zero!'

# Выведет 'Division by zero!'.

print(res)

res = True if 'a' in 'abc' else False

# Выведет True.

print(res)False

Division by zero!

True

Пример №5. Использование трехместного выражения if/else (часть 2).

Рассмотренные нами примеры достаточно просты, поэтому получившиеся трехместные выражения легко поместились в одну строку. В более сложных случаях, когда выражения получаются громоздкими и

читабельность кода падает, лучше не мудрить, а использовать полноценную условную инструкцию if/else.

Краткие итоги параграфа

-

Условная инструкция if/elif/else дает нам возможность изменить ход программы за счет выполнения только одного определенного блока инструкций,

соответствующего первому попавшемуся ключевому слову с истинным условием. Обязательным является только ключевое слово if, остальные ключевые слова

конструкции могут быть опущены. При этом разрешается использовать любое количество ключевых слов elif, но только одно ключевое слово

else. -

Так как в Python использовать инструкции непосредственно в выражениях не разрешается, для проверки условий в них было введено специальное трехместное

выражение if/else. Его еще называют тернарным оператором if/else. В общем виде конструкцию можно представить как

A = Y if X else Z. Вычисления здесь выполняются по сокращенной схеме: интерпретатор обрабатывает выражение Y, только

если условие X истинно, а выражение Z обрабатывается, только если условие X ложно.

Вопросы и задания для самоконтроля

1. Какие из частей условной инструкции if/elif/else не являются обязательными?

Показать решение.

Ответ. Обязательным является только блок if, блоки elif и

else используются по необходимости.

2. Как в языке Python можно оформить множественное ветвление?

Показать решение.

Ответ. Прямым способом оформления множественного ветвления следует считать использование инструкции if с

несколькими блоками elif, т.к. в Python отсутствует инструкция switch, которая

присутствует в некоторых других языках программирования (например, PHP).

3. Какой из представленных форматов соответствует условной инструкции: if/elseif/else,

if/elif/else, A = Y if X else Z?

Показать решение.

Ответ. if/elif/else.

4. Исправьте в коде три ошибки.

Показать решение.

a = 3547

b = 155

if a/b > 25

print('a/b > 25')

else if a/b > 15:

print('a/b > 15')

else:

print('a/b <= 15'a = 3547

b = 155

if a/b > 25

print('a/b > 25')

else if a/b > 15:

print('a/b > 15')

else:

print('a/b <= 15'

a = 3547

b = 155

# Не забываем про двоеточие.

if a/b > 25:

print('a/b > 25')

# Правильно elif.

elif a/b > 15:

print('a/b > 15')

else:

# А где закрывающая скобка?

print('a/b <= 15')

5. Дополнительные упражнения и задачи по теме расположены в разделе

«Алгоритмы ветвления»

нашего сборника задач и упражнений по языку программирования Python.

Быстрый переход к другим страницам

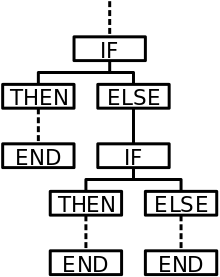

If-then-else flow diagram

A nested if–then–else flow diagram

In computer science, conditionals (that is, conditional statements, conditional expressions and conditional constructs) are programming language commands for handling decisions. Specifically, conditionals perform different computations or actions depending on whether a programmer-defined Boolean condition evaluates to true or false. In terms of control flow, the decision is always achieved by selectively altering the control flow based on some condition (apart from the case of branch predication).

Although dynamic dispatch is not usually classified as a conditional construct, it is another way to select between alternatives at runtime.

Terminology[edit]

In imperative programming languages, the term «conditional statement» is usually used, whereas in functional programming, the terms «conditional expression» or «conditional construct» are preferred, because these terms all have distinct meanings.

If–then(–else)[edit]

«if-then-else» redirects here. For the album, see If Then Else.

The if–then construct (sometimes called if–then–else) is common across many programming languages. Although the syntax varies from language to language, the basic structure (in pseudocode form) looks like this:

If (boolean condition) Then (consequent) Else (alternative) End If

For example:

If stock=0 Then message= order new stock Else message= there is stock End If

In the example code above, the part represented by (boolean condition) constitutes a conditional expression, having intrinsic value (e.g., it may be substituted by either of the values True or False) but having no intrinsic meaning. In contrast, the combination of this expression, the If and Then surrounding it, and the consequent that follows afterward constitute a conditional statement, having intrinsic meaning (e.g., expressing a coherent logical rule) but no intrinsic value.

When an interpreter finds an If, it expects a Boolean condition – for example, x > 0, which means «the variable x contains a number that is greater than zero» – and evaluates that condition. If the condition is true, the statements following the then are executed. Otherwise, the execution continues in the following branch – either in the else block (which is usually optional), or if there is no else branch, then after the end If.

After either branch has been executed, control returns to the point after the end If.

History and development[edit]

In early programming languages, especially some dialects of BASIC in the 1980s home computers, an if–then statement could only contain GOTO statements (equivalent to a branch instruction). This led to a hard-to-read style of programming known as spaghetti programming, with programs in this style called spaghetti code. As a result, structured programming, which allows (virtually) arbitrary statements to be put in statement blocks inside an if statement, gained in popularity, until it became the norm even in most BASIC programming circles. Such mechanisms and principles were based on the older but more advanced ALGOL family of languages, and ALGOL-like languages such as Pascal and Modula-2 influenced modern BASIC variants for many years. While it is possible while using only GOTO statements in if–then statements to write programs that are not spaghetti code and are just as well structured and readable as programs written in a structured programming language, structured programming makes this easier and enforces it. Structured if–then–else statements like the example above are one of the key elements of structured programming, and they are present in most popular high-level programming languages such as C, Java, JavaScript and Visual Basic .

The «dangling else» problem[edit]

The else keyword is made to target a specific if–then statement preceding it, but for nested if–then statements, classic programming languages such as ALGOL 60 struggled to define which specific statement to target. Without clear boundaries for which statement is which, an else keyword could target any preceding if–then statement in the nest, as parsed.

if a then if b then s else s2

can be parsed as

if a then (if b then s) else s2

or

if a then (if b then s else s2)

depending on whether the else is associated with the first if or second if. This is known as the dangling else problem, and is resolved in various ways, depending on the language (commonly via the end if statement or {...} brackets).

Else if[edit]

By using else if, it is possible to combine several conditions. Only the statements following the first condition that is found to be true will be executed. All other statements will be skipped.

if condition then -- statements elseif condition then -- more statements elseif condition then -- more statements; ... else -- other statements; end if;

For example, for a shop offering as much as a 30% discount for an item:

if discount < 11% then print (you have to pay $30) elseif discount<21% then print (you have to pay $20) elseif discount<31% then print (you have to pay $10) end if;

In the example above, if the discount is 10%, then the first if statement will be evaluated as true and «you have to pay $30» will be printed out. All other statements below that first if statement will be skipped.

The elseif statement, in the Ada language for example, is simply syntactic sugar for else followed by if. In Ada, the difference is that only one end if is needed, if one uses elseif instead of else followed by if. PHP uses the elseif keyword[1] both for its curly brackets or colon syntaxes. Perl provides the keyword elsif to avoid the large number of braces that would be required by multiple if and else statements. Python uses the special keyword elif because structure is denoted by indentation rather than braces, so a repeated use of else and if would require increased indentation after every condition. Some implementations of BASIC, such as Visual Basic,[2] use ElseIf too. Similarly, the earlier UNIX shells (later gathered up to the POSIX shell syntax[3]) use elif too, but giving the choice of delimiting with spaces, line breaks, or both.

However, in many languages more directly descended from Algol, such as Simula, Pascal, BCPL and C, this special syntax for the else if construct is not present, nor is it present in the many syntactical derivatives of C, such as Java, ECMAScript, and so on. This works because in these languages, any single statement (in this case if cond…) can follow a conditional without being enclosed in a block.

This design choice has a slight «cost». Each else if branch effectively adds an extra nesting level. This complicates the job for the compiler (or the people who write the compiler), because the compiler must analyse and implement arbitrarily long else if chains recursively.

If all terms in the sequence of conditionals are testing the value of a single expression (e.g., if x=0 … else if x=1 … else if x=2…), an alternative is the switch statement, also called case-statement or select-statement. Conversely, in languages that do not have a switch statement, these can be produced by a sequence of else if statements.

If–then–else expressions[edit]

Many languages support if expressions, which are similar to if statements, but return a value as a result. Thus, they are true expressions (which evaluate to a value), not statements (which may not be permitted in the context of a value).

Algol family[edit]

ALGOL 60 and some other members of the ALGOL family allow if–then–else as an expression:

myvariable := if x > 20 then 1 else 2

Lisp dialects[edit]

In dialects of Lisp – Scheme, Racket and Common Lisp – the first of which was inspired to a great extent by ALGOL:

;; Scheme (define myvariable (if (> x 12) 1 2)) ; Assigns 'myvariable' to 1 or 2, depending on the value of 'x'

;; Common Lisp (let ((x 10)) (setq myvariable (if (> x 12) 2 4))) ; Assigns 'myvariable' to 2

Haskell[edit]

In Haskell 98, there is only an if expression, no if statement, and the else part is compulsory, as every expression must have some value.[4] Logic that would be expressed with conditionals in other languages is usually expressed with pattern matching in recursive functions.

Because Haskell is lazy, it is possible to write control structures, such as if, as ordinary expressions; the lazy evaluation means that an if function can evaluate only the condition and proper branch (where a strict language would evaluate all three). It can be written like this:[5]

if' :: Bool -> a -> a -> a if' True x _ = x if' False _ y = y

C-like languages[edit]

C and C-like languages have a special ternary operator (?:) for conditional expressions with a function that may be described by a template like this:

condition ? evaluated-when-true : evaluated-when-false

This means that it can be inlined into expressions, unlike if-statements, in C-like languages:

my_variable = x > 10 ? "foo" : "bar"; // In C-like languages

which can be compared to the Algol-family if–then–else expressions (in contrast to a statement) (and similar in Ruby and Scala, among others).

To accomplish the same using an if-statement, this would take more than one line of code (under typical layout conventions), and require mentioning «my_variable» twice:

if (x > 10) my_variable = "foo"; else my_variable = "bar";

Some argue that the explicit if/then statement is easier to read and that it may compile to more efficient code than the ternary operator,[6] while others argue that concise expressions are easier to read than statements spread over several lines containing repetition.

Small Basic[edit]

x = TextWindow.ReadNumber() If (x > 10) Then TextWindow.WriteLine("My variable is named 'foo'.") Else TextWindow.WriteLine("My variable is named 'bar'.") EndIf

First, when the user runs the program, a cursor appears waiting for the reader to type a number. If that number is greater than 10, the text «My variable is named ‘foo’.» is displayed on the screen. If the number is smaller than 10, then the message «My variable is named ‘bar’.» is printed on the screen.

Visual Basic[edit]

In Visual Basic and some other languages, a function called IIf is provided, which can be used as a conditional expression. However, it does not behave like a true conditional expression, because both the true and false branches are always evaluated; it is just that the result of one of them is thrown away, while the result of the other is returned by the IIf function.

Tcl[edit]

In Tcl if is not a keyword but a function (in Tcl known as command or proc). For example

if {$x > 10} { puts "Foo!" }

invokes a function named if passing 2 arguments: The first one being the condition and the second one being the true branch. Both arguments are passed as strings (in Tcl everything within curly brackets is a string).

In the above example the condition is not evaluated before calling the function. Instead, the implementation of the if function receives the condition as a string value and is responsible to evaluate this string as an expression in the callers scope.[7]

Such a behavior is possible by using uplevel and expr commands:

- Uplevel makes it possible to implement new control constructs as Tcl procedures (for example, uplevel could be used to implement the while construct as a Tcl procedure).[8]

Because if is actually a function it also returns a value:

- The return value from the command is the result of the body script that was executed, or an empty string if none of the expressions was non-zero and there was no bodyN.[9]

Rust[edit]

In Rust, if is always an expression. It evaluates to the value of whichever branch is executed, or to the unit type () if no branch is executed. If a branch does not provide a return value, it evaluates to () by default. To ensure the if expression’s type is known at compile time, each branch must evaluate to a value of the same type. For this reason, an else branch is effectively compulsory unless the other branches evaluate to (), because an if without an else can always evaluate to () by default.[10]

// Assign my_variable some value, depending on the value of x let my_variable = if x > 20 { 1 } else { 2 }; // This variant will not compile because 1 and () have different types let my_variable = if x > 20 { 1 }; // Values can be omitted when not needed if x > 20 { println!("x is greater than 20"); }

Arithmetic if[edit]

Up to Fortran 77, the language Fortran has an «arithmetic if» statement which is halfway between a computed IF and a case statement, based on the trichotomy x < 0, x = 0, x > 0. This was the earliest conditional statement in Fortran:[11]

IF (e) label1, label2, label3

Where e is any numeric expression (not necessarily an integer); this is equivalent to

IF (e .LT. 0) GOTO label1 IF (e .EQ. 0) GOTO label2 GOTO label3

Because this arithmetic IF is equivalent to multiple GOTO statements that could jump to anywhere, it is considered to be an unstructured control statement, and should not be used if more structured statements can be used. In practice it has been observed that most arithmetic IF statements referenced the following statement with one or two of the labels.

This was the only conditional control statement in the original implementation of Fortran on the IBM 704 computer. On that computer the test-and-branch op-code had three addresses for those three states. Other computers would have «flag» registers such as positive, zero, negative, even, overflow, carry, associated with the last arithmetic operations and would use instructions such as ‘Branch if accumulator negative’ then ‘Branch if accumulator zero’ or similar. Note that the expression is evaluated once only, and in cases such as integer arithmetic where overflow may occur, the overflow or carry flags would be considered also.

Object-oriented implementation in Smalltalk[edit]

In contrast to other languages, in Smalltalk the conditional statement is not a language construct but defined in the class Boolean as an abstract method that takes two parameters, both closures. Boolean has two subclasses, True and False, which both define the method, True executing the first closure only, False executing the second closure only.[12]

var = condition ifTrue: [ 'foo' ] ifFalse: [ 'bar' ]

JavaScript[edit]

JavaScript uses if-else statements similar to those in C languages. A Boolean value is accepted within parentheses between the reserved if keyword and a left curly bracket.

if (Math.random() < 0.5) { console.log("You got Heads!"); } else { console.log("You got Tails!"); }

The above example takes the conditional of Math.random() < 0.5 which outputs true if a random float value between 0 and 1 is greater than 0.5. The statement uses it to randomly choose between outputting You got Heads! or You got Tails! to the console. Else and else-if statements can also be chained after the curly bracket of the statement preceding it as many times as necessary, as shown below:

var x = Math.random(); if (x < 1/3) { console.log("One person won!"); } else if (x < 2/3) { console.log("Two people won!"); } else { console.log("It's a three-way tie!"); }

Lambda calculus[edit]

In Lambda calculus, the concept of an if-then-else conditional can be expressed using the following expressions:

true = λx. λy. x false = λx. λy. y ifThenElse = (λc. λx. λy. (c x y))

- true takes up to two arguments and once both are provided (see currying), it returns the first argument given.

- false takes up to two arguments and once both are provided(see currying), it returns the second argument given.

- ifThenElse takes up to three arguments and once all are provided, it passes both second and third argument to the first argument(which is a function that given two arguments, and produces a result). We expect ifThenElse to only take true or false as an argument, both of which project the given two arguments to their preferred single argument, which is then returned.

note: if ifThenElse is passed two functions as the left and right conditionals; it is necessary to also pass an empty tuple () to the result of ifThenElse in order to actually call the chosen function, otherwise ifThenElse will just return the function object without getting called.

In a system where numbers can be used without definition (like Lisp, Traditional paper math, so on), the above can be expressed as a single closure below:

((λtrue. λfalse. λifThenElse. (ifThenElse true 2 3) )(λx. λy. x)(λx. λy. y)(λc. λl. λr. c l r))

Here, true, false, and ifThenElse are bound to their respective definitions which are passed to their scope at the end of their block.

A working JavaScript analogy(using only functions of single variable for rigor) to this is as follows:

var computationResult = ((_true => _false => _ifThenElse => _ifThenElse(_true)(2)(3) )(x => y => x)(x => y => y)(c => x => y => c(x)(y)));

The code above with multivariable functions looks like this:

var computationResult = ((_true, _false, _ifThenElse) => _ifThenElse(_true, 2, 3) )((x, y) => x, (x, y) => y, (c, x, y) => c(x, y));

Another version of the earlier example without a system where numbers are assumed is below.

The first example shows the first branch being taken, while second example shows the second branch being taken.

((λtrue. λfalse. λifThenElse. (ifThenElse true (λFirstBranch. FirstBranch) (λSecondBranch. SecondBranch)) )(λx. λy. x)(λx. λy. y)(λc. λl. λr. c l r)) ((λtrue. λfalse. λifThenElse. (ifThenElse false (λFirstBranch. FirstBranch) (λSecondBranch. SecondBranch)) )(λx. λy. x)(λx. λy. y)(λc. λl. λr. c l r))

Smalltalk uses a similar idea for its true and false representations, with True and False being singleton objects that respond to messages ifTrue/ifFalse differently.

Haskell used to use this exact model for its Boolean type, but at the time of writing, most Haskell programs use syntactic sugar «if a then b else c» construct which unlike ifThenElse does not compose unless

either wrapped in another function or re-implemented as shown in The Haskell section of this page.

Case and switch statements[edit]

Switch statements (in some languages, case statements or multiway branches) compare a given value with specified constants and take action according to the first constant to match. There is usually a provision for a default action (‘else’,’otherwise’) to be taken if no match succeeds. Switch statements can allow compiler optimizations, such as lookup tables. In dynamic languages, the cases may not be limited to constant expressions, and might extend to pattern matching, as in the shell script example on the right, where the ‘*)’ implements the default case as a regular expression matching any string.

| Pascal: | C: | Shell script: |

|---|---|---|

case someChar of 'a': actionOnA; 'x': actionOnX; 'y','z':actionOnYandZ; else actionOnNoMatch; end; |

switch (someChar) { case 'a': actionOnA; break; case 'x': actionOnX; break; case 'y': case 'z': actionOnYandZ; break; default: actionOnNoMatch; } |

case $someChar in a) actionOnA; ;; x) actionOnX; ;; [yz]) actionOnYandZ; ;; *) actionOnNoMatch ;; esac |

Pattern matching[edit]

Pattern matching may be seen as an alternative to both if–then–else, and case statements. It is available in many programming languages with functional programming features, such as Wolfram Language, ML and many others. Here is a simple example written in the OCaml language:

match fruit with | "apple" -> cook pie | "coconut" -> cook dango_mochi | "banana" -> mix;;

The power of pattern matching is the ability to concisely match not only actions but also values to patterns of data. Here is an example written in Haskell which illustrates both of these features:

map _ [] = [] map f (h : t) = f h : map f t

This code defines a function map, which applies the first argument (a function) to each of the elements of the second argument (a list), and returns the resulting list. The two lines are the two definitions of the function for the two kinds of arguments possible in this case – one where the list is empty (just return an empty list) and the other case where the list is not empty.

Pattern matching is not strictly speaking always a choice construct, because it is possible in Haskell to write only one alternative, which is guaranteed to always be matched – in this situation, it is not being used as a choice construct, but simply as a way to bind names to values. However, it is frequently used as a choice construct in the languages in which it is available.

Hash-based conditionals[edit]

In programming languages that have associative arrays or comparable data structures, such as Python, Perl, PHP or Objective-C, it is idiomatic to use them to implement conditional assignment.[13]

pet = input("Enter the type of pet you want to name: ") known_pets = { "Dog": "Fido", "Cat": "Meowsles", "Bird": "Tweety", } my_name = known_pets[pet]

In languages that have anonymous functions or that allow a programmer to assign a named function to a variable reference, conditional flow can be implemented by using a hash as a dispatch table.

Predication[edit]

An alternative to conditional branch instructions is predication. Predication is an architectural feature that enables instructions to be conditionally executed instead of modifying the control flow.

Choice system cross reference[edit]

This table refers to the most recent language specification of each language. For languages that do not have a specification, the latest officially released implementation is referred to.

| Programming language | Structured if | switch–select–case | Arithmetic if | Pattern matching[A] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| then | else | else–if | ||||

| Ada | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| APL | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Bash shell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| C, C++ | No | Yes | unneeded[B][C] | Fall-through | No | No |

| C# | No | Yes | Unneeded[B][C] | Yes | No | No |

| COBOL | Yes | Yes | Unneeded[C] | Yes | No | No |

| Eiffel | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| F# | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unneeded[D] | No | Yes |

| Fortran 90 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[G] | No |

| Go | No | Yes | Unneeded[C] | Yes | No | No |

| Haskell | Yes | Needed | Unneeded[C] | Yes, but unneeded[D] | No | Yes |

| Java | No | Yes | Unneeded[C] | Fall-through[14] | No | No |

| ECMAScript (JavaScript) | No | Yes | Unneeded[C] | Fall-through[15] | No | No |

| Mathematica | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Oberon | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Perl | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| PHP | No | Yes | Yes | Fall-through | No | No |

| Pascal, Object Pascal (Delphi) | Yes | Yes | Unneeded | Yes | No | No |

| Python | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| QuickBASIC | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Ruby | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes[H] |

| Rust | No | Yes | Yes | Unneeded | No | Yes |

| Scala | No | Yes | Unneeded[C] | Fall-through[citation needed] | No | Yes |

| SQL | Yes[F] | Yes | Yes | Yes[F] | No | No |

| Swift | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Tcl | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Visual Basic, classic | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Visual Basic .NET | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Windows PowerShell | No | Yes | Yes | Fall-through | No | No |

- ^ This refers to pattern matching as a distinct conditional construct in the programming language – as opposed to mere string pattern matching support, such as regular expression support.

- 1 2 An #ELIF directive is used in the preprocessor sub-language that is used to modify the code before compilation; and to include other files.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The often-encountered

else ifin the C family of languages, and in COBOL and Haskell, is not a language feature but a set of nested and independent if then else statements combined with a particular source code layout. However, this also means that a distinct else–if construct is not really needed in these languages. - 1 2 In Haskell and F#, a separate constant choice construct is unneeded, because the same task can be done with pattern matching.

- ^ In a Ruby

caseconstruct, regular expression matching is among the conditional flow-control alternatives available. For an example, see this Stack Overflow question. - 1 2 SQL has two similar constructs that fulfill both roles, both introduced in SQL-92. A «searched

CASE» expressionCASE WHEN cond1 THEN expr1 WHEN cond2 THEN expr2 [...] ELSE exprDflt ENDworks likeif ... else if ... else, whereas a «simpleCASE» expression:CASE expr WHEN val1 THEN expr1 [...] ELSE exprDflt ENDworks like a switch statement. For details and examples see Case (SQL). - ^ Arithmetic

ifis obsolescent in Fortran 90. - ^ Pattern matching was added in Ruby 3.0.[16] Some pattern matching constructs are still experimental.

See also[edit]

- Branch (computer science)

- Conditional compilation

- Dynamic dispatch for another way to make execution choices

- McCarthy Formalism for history and historical references

- Named condition

- Relational operator

- Test (Unix)

- Yoda conditions

- Conditional move

References[edit]

- ^ PHP elseif syntax

- ^ Visual Basic ElseIf syntax

- ^ POSIX standard shell syntax

- ^ Haskell 98 Language and Libraries: The Revised Report

- ^ «If-then-else Proposal on HaskellWiki»

- ^ «Efficient C Tips #6 – Don’t use the ternary operator « Stack Overflow». Embeddedgurus.com. 2009-02-18. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- ^ «New Control Structures». Tcler’s wiki. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ «uplevel manual page». www.tcl.tk. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ «if manual page». www.tcl.tk. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ «If and if let expressions». Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ «American National Standard Programming Language FORTRAN». 1978-04-03. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ^ «VisualWorks: Conditional Processing». 2006-12-16. Archived from the original on 2007-10-22. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ^ «Pythonic way to implement switch/case statements». Archived from the original on 2015-01-20. Retrieved 2015-01-19.

- ^ Java.sun.com, Java Language Specification, 3rd Edition.

- ^ Ecma-international.org Archived 2015-04-12 at the Wayback Machine ECMAScript Language Specification, 5th Edition.

- ^ «Pattern Matching». Documentation for Ruby 3.0.

External links[edit]

Look up then or else in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Media related to Conditional (computer programming) at Wikimedia Commons

- IF NOT (ActionScript 3.0) video

В первой главе мы научились писать программы, в которых выполнялись все строки. Однако очень часто нам нужно, чтобы код выполнялся при определённых условиях. В таком случае используется условный оператор.

Рассмотрим его синтаксис на примере. Пусть от пользователя требуется ввести два целых числа: температуру на улице вчера и сегодня. А программа ответит — сегодня теплее, холоднее или же температура не изменилась:

yesterday_temp = int(input())

today_temp = int(input())

if today_temp > yesterday_temp:

print("Сегодня теплее, чем вчера.")

elif today_temp < yesterday_temp:

print("Сегодня холоднее, чем вчера.")

else:

print("Сегодня такая же температура, как вчера.")

Оператор if является началом условной конструкции. Далее идёт условие, которое возвращает логическое значение True (истина) или False (ложь). Завершается условие символом «двоеточие». Затем — обязательный отступ в четыре пробела, он показывает, что строки объединяются в один блок. Отступ аналогичен использованию фигурных скобок или ключевых слов begin и end в других языках программирования.

Тело условной конструкции может содержать одно или несколько выражений (строк). По завершении тела может идти следующее условие, которое начинается с оператора elif (сокращение от else if — «иначе если»). Оно проверяется только в случае, если предыдущее условие не было истинным.

Синтаксис в elif аналогичен if. Операторов elif для одного блока условного оператора может быть несколько, а может не быть совсем. Последним идёт оператор else, который не содержит условия, а выполняется, только если ни одно из предыдущих условий в if и elif не выполнилось. Оператор else не является обязательным.

В качестве условия может выступать результат операции сравнения:

>(больше);>=(больше или равно);<(меньше);<=(меньше или равно);==(равно);!=(не равно).

Для записи сложных условий можно применять логические операции:

and— логическое «И» для двух условий. ВозвращаетTrue, если оба условия истинны, иначе возвращаетFalse;or— логическое «ИЛИ» для двух условий. ВозвращаетFalse, если оба условия ложны, иначе возвращаетTrue;not— логическое «НЕ» для одного условия. ВозвращаетFalseдля истинного условия, и наоборот.

Ниже приведена таблица истинности для логических операций.

| x | y | not x | x or y | x and y |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| False | False | True | False | False |

| False | True | True | True | False |

| True | False | False | True | False |

| True | True | False | True | True |

Рассмотрим следующий пример. Пользователь должен ввести первую и последнюю буквы русского алфавита. Ввод производится в двух отдельных строках и в любом регистре.

print("Введите первую и последнюю буквы русского алфавита.")

first_letter = input()

last_letter = input()

if (first_letter == "а" or first_letter == "А") and (

last_letter == "я" or last_letter == "Я"):

print("Верно.")

else:

print("Неверно.")

В логическом операторе можно использовать двойное неравенство. Например, неравенство

if x >= 0 and x < 100:

...

лучше записать так:

if 0 <= x < 100:

...

Строки также можно сравнивать между собой с помощью операций >, < и т. д. В отличие от чисел, строки сравниваются посимвольно в соответствии с кодами символов в таблице кодировки (в Python рекомендуется использовать кодировку UTF-8).

Компьютер изначально работает только с двоичными числами. Поэтому для работы с символами им назначаются коды — числа, а сами таблицы соответствия символов и кодов называются таблицами кодировки. Кодировок существует достаточно много, одной из самых популярных на данный момент является UTF-8. Например, сравним две односимвольные строки:

letter_1 = "t"

letter_2 = "w"

print(letter_1 > letter_2)

Программа выведет False, поскольку символ t стоит в таблице кодировки раньше, чем w (как и по алфавиту, то есть лексикографически). Чтобы убедиться в этом, можно использовать встроенную функцию ord(), которая возвращает код символа из таблицы кодировки:

print(ord("t"), ord("w"))

В консоли отобразится:

116 119

Поскольку 116 меньше 119, в предыдущем примере мы и получили False.

Чтобы получить символ по его коду, необходимо вызвать встроенную функцию chr() с соответствующим кодом:

print(chr(116), chr(119))

В результате увидим:

t w

В таблице кодировки большие и маленькие буквы являются различными символами с разными кодами (из разных диапазонов). Поэтому для корректного сравнения строки должны быть в одном регистре.

Для проверки условия наличия подстроки в строке (и для некоторых других вещей, о которых будет рассказано позже) используется оператор in. Например, проверим, что во введённой строке встречается корень «добр» (для слов «добрый», «доброе» и подобных):

text = input()

if "добр" in text:

print("Встретилось 'доброе' слово.")

else:

print("Добрых слов не найдено.")

В Python версии 3.10 появился оператор match. В простейшем случае он последовательно сравнивает значение выражения с заранее заданными в операторах case. А затем выполняет код в операторе case, значение в котором соответствует проверяемому. Напишем программу, которая сравнивает значение текущего сигнала светофора с одним из трёх вариантов (красный, жёлтый или зелёный):

color = input()

match color:

case 'красный' | 'жёлтый':

print('Стоп.')

case 'зелёный':

print('Можно ехать.')

case _:

print('Некорректное значение.')

Обратите внимание, что для проверки выполнения условия «ИЛИ» в операторе case не используется логическая операция or. Её нельзя использовать, поскольку она применяется для переменных логического типа, а в примере перечисляются значения-строки. Вместо неё мы используем специальный оператор |.

Последний оператор case выполняется всегда и сработает в случае, если ни одно из предыдущих условий не сработало. Оператор match похож на оператор switch других языков программирования — C++, JavaScript и т. д.

Рассмотрим некоторые полезные встроенные функции.

- Для определения длины строки (а также других коллекций, о которых будет рассказано позже) используется функция

len(). - Для определения максимального и минимального из нескольких значений (не только числовых) используются функции

max()иmin()соответственно. - Функция

abs()используется для определения модуля числа.

Рассмотрим применение встроенных функций в следующем примере. Обратите внимание на строки, начинающиеся со знака #. Так в Python обозначаются комментарии — линии, которые не выполняются интерпретатором, а служат для пояснения кода.

m = 12

n = 19

k = 25

# максимальное число

print(max(m, n, k))

line_1 = "m"

line_2 = "n"

line_3 = "k"

# минимальная лексикографически строка

print(min(line_1, line_2, line_3))

# количество цифр в числе 2 в степени 2022

print(len(str(2 ** 2022)))

В следующей теме вы узнаете о циклах — конструкциях, которые позволяют выполнять один и тот же код несколько раз. Для этой главы мы также подготовили задачи. Не пропускайте их, если хотите закрепить материал.

Ещё по теме

- Оператор

matchтакже используется для так называемой проверки шаблона (pattern matching), почитать о которой можно в этом материале. - Все доступные в Python встроенные функции можно посмотреть на этой странице.

Чтобы эффективно работать с условными операторами на языке Java, необходимо знать, какими они бывают и для каких сценариев подходят. Обсудим это и некоторые нововведения из Java 13.

- if

- if-else

- Вложенный if

- «Элвис»

- switch

- Задачи на условные операторы

Оператор if позволяет задать условие, в соответствии с которым дальнейшая часть программы может быть выполнена. Это основной оператор выбора, который используется в языке Java. Он начинается с ключевого слова if и продолжается булевым выражением — условием, заключённым в круглые скобки.

В качестве примера рассмотрим простое равенство, при истинности которого программа выведет результат:

if(2 * 2 == 4){

System.out.println("Программа выполняется");

}Поскольку условие истинно, в выводе программы мы увидим:

Программа выполняетсяУсловный оператор if-else в Java

else в языке Java означает «в ином случае». То есть если условие if не является истинным, выводится то, что в блоке else:

if(2 * 2 == 5){

System.out.println("Программа выполняется");

} else{

System.out.println("Условие ошибочно");

}Вывод:

Условие ошибочноЭто же сработает и без ключевого слова else, но чтобы код был читабельным и логичным, не следует пренебрегать else, как это сделано в следующем примере:

if(2 * 2 == 5){

System.out.println("Программа выполняется");

}

System.out.println("Условие ошибочно");А теперь давайте создадим несколько условий с использованием конструкции if-else. Выглядит это таким образом:

int a = 20;

if(a == 10){

System.out.println("a = 10");

} else if(a == 15){

System.out.println("a = 15");

} else if(a == 20){

System.out.println("a = 20");

} else{

System.out.println("Ничего из перечисленного");

}Вывод:

a = 20Как видим, только третье условие истинно, поэтому выводится именно a = 20, а все остальные блоки игнорируются.

Вложенный if

Кроме того, может производиться проверка сразу на несколько условий, в соответствии с которыми выполняются разные действия. Представим, что у нас есть две переменные, на основе которых можно создать два условия:

int a = 20;

int b = 5;

if(a == 20){

System.out.println("a = 20");

if(b == 5){

System.out.println("b = 5");

}

}Вывод:

a = 20

b = 5В результате программа заходит в оба блока и делает два вывода, потому как оба условия истинны.

«Элвис»

По сути, это сокращенный вариант if-else. Элвисом его прозвали за конструкцию, которая напоминает причёску короля рок-н-ролла — ?:. Данный оператор также принято называть тернарным. Он требует три операнда и позволяет писать меньше кода для простых условий.

Само выражение будет выглядеть следующим образом:

int a = 20;

int b = 5;

String answer = (a > b) ? "Условие верно" : "Условие ошибочно";

System.out.println(answer);Вывод:

Условие верноКак видите, с помощью тернарного оператора можно существенно сократить код. Но не стоит им злоупотреблять: для сложных условий используйте другие операторы выбора Java, дабы не ухудшать читаемость кода.

Условный оператор switch в Java

Оператор выбора switch позволяет сравнивать переменную как с одним, так и с несколькими значениями. Общая форма написания выглядит следующим образом:

switch(выражение) {

case значение1:

// Блок кода 1

break;

case значение2:

// Блок кода 2

break;

case значениеN:

// Блок кода N

break;

default :

// Блок кода для default

}Рассмотрим распространённый пример с днями недели:

public class Main {

//Создадим простое перечисление дней недели

private static enum DayOTheWeek{

MON, TUE, WED, THU, FRI, SAT, SUN

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

//Выбираем понедельник (MON)

var dayOfTheWeek= DayOTheWeek.MON;

switch (dayOfTheWeek){

case MON:

System.out.println("Понедельник");

break;

case TUE:

System.out.println("Вторник");

break;

default:

System.out.println("Другой день недели");

}

}

}Вывод:

Понедельникbreak при этом прерывает процесс проверки, поскольку соответствие условия уже найдено. Но начиная с Java 13, вместо break в условном операторе switch правильнее использовать yield — ключевое слово, которое не только завершает проверку, но и возвращает значение блока.

Кроме того, с 12 версии Java конструкция switch-case также претерпела некоторые изменения. Если вы используете в работе IntelliJ IDEA, данная среда разработки сама подскажет, как оптимизировать switch-case под новые версии.

Вот преобразованный код из нашего примера с некоторыми изменениями:

public class Main {

private static enum DayOTheWeek{

MON, TUE, WED, THU, FRI, SAT, SUN

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

//В этот раз выберем вторник

var dayOfTheWeek= DayOTheWeek.TUE;

String result = switch (dayOfTheWeek){

case MON -> "Понедельник";

case TUE, WED, THU, FRI -> {

yield "Любой будний день, кроме понедельника.";

}

default -> "Выходной день";

};

System.out.println(result);

}

}Вывод:

Любой будний день, кроме понедельника.Задачи на условные операторы Java

Определите, что выведут в консоль следующие примеры, без проверки в компиляторе.

1. В переменной min лежит число от 0 до 59. Определите в какую четверть часа попадает это число (в первую, вторую, третью или четвертую):

int min = 10;

if(min >= 0 && min <= 14){

System.out.println("В первую четверть.");

}

else if(min >= 15 && min <= 30){

System.out.println("Во вторую четверть.");

}

else if(min >= 31 && min <= 45){

System.out.println("В третью четверть.");

}

else{

System.out.println("В четвертую четверть.");

}2. Что выведет следующий код:

int month = 3;

String monthString;

switch (month) {

case 1: monthString = "Январь";

break;

case 2: monthString = "Февраль";

break;

case 3: monthString = "Март";

break;

case 4: monthString = "Апрель";

break;

case 5: monthString = "Май";

break;

case 6: monthString = "Июнь";

break;

case 7: monthString = "Июль";

break;

case 8: monthString = "Август";

break;

case 9: monthString = "Сентябрь";

break;

case 10: monthString = "Октябрь";

break;

case 11: monthString = "Ноябрь";

break;

case 12: monthString = "Декабрь";

break;

default: monthString = "Не знаем такого";

break;

}

System.out.println(monthString);3. Какое значение будет присвоено переменной k:

int i = -10 * -1 + (-2);

int k = i < 0 ? -i : i;

System.out.println(k);Пишите свои ответы к задачам по условным операторам в Java.