Без регулярного серьёзного финансирования его движения, оплаты ряда дорогостоящих мероприятий, которые сделали Немецкую национал-социалистическую рабочую партию (в немецкой транскрипции НСДАП) популярной, нацисты никогда бы не достигли вершин власти, оставаясь обычным среди десятков подобных движений местного значения. Для тех, кто серьёзно исследовал и исследует феномен национал-социализма и фюрера, это факт.

Главными спонсорами Гитлера и его партии выступили финансисты Великобритании и Соединенных Штатов. С самого начала Гитлер был «проектом». Энергичный фюрер был инструментом для объединения Европы против Советского Союза, решались также и другие важные задачи, так, прошли полигонные испытания «Нового мирового порядка», который планировали распространить по всей планете. Спонсировали Гитлера и германские финансово-промышленные круги, связанные с мировым финансовым интернационалом. Среди спонсоров Гитлера был Фриц Тиссен (старший сын промышленника Августа Тиссена), он ещё с 1923 года оказывал значительную материальную поддержку нацистам, в 1930 году публично поддержал Гитлера. В 1932 году входил в группу финансистов, промышленников и землевладельцев, которые потребовали от рейхспрезидента Пауля фон Гинденбурга назначить Гитлера рейхсканцлером. Тиссен был сторонником восстановления сословного государства — в мае 1933 года он при поддержке Гитлера учредил в Дюссельдорфе Институт сословий. Тиссен планировал подвести научную базу под идеологию сословного государства. Тиссен был сторонником войны с СССР, но протестовал против войны с западными странами и выступал против преследования евреев. В итоге последовал разрыв отношений с Гитлером. 2 сентября 1939 года Тиссен уехал вместе со своей женой, дочерью и зятем в Швейцарию. В 1940 году во Франции он написал книгу «Я финансировал Гитлера», после оккупации французского государства арестован и попал в концлагерь, где пробыл до конца войны.

Финансовую помощь нацистам оказывал германский промышленник и финансовый магнат Густав Крупп. Среди банкиров деньги для Гитлера собирал президент Рейхсбанка и доверенное лицо Адольфа Гитлера по связям с его политическими и финансовыми спонсорами в западных странах Ялмар Шахт. Этот талантливый организатор с 1916 года возглавлял частный Национальный банк Германии, затем стал его совладельцем. С декабря 1923 года — глава Рейхсбанка (руководил до марта 1930 года, а затем в 1933-1939 годы). Имел плотные связи с американской корпорацией Дж.П.Моргана. Именно он с 1933 года проводил экономическую мобилизацию Германии, готовя её к войне.

Причины, которые заставили германскую финансово-промышленную элиту помогать Гитлеру и его партии, были самыми разными. Одни хотели создать мощную ударную силу против внутренней «коммунистической угрозы» и рабочего движения. Боялись и внешней опасности – «большевистской угрозы». Другие перестраховывались на случай прихода Гитлера к власти. Третьи работали в одной группе с мировым финансовым интернационалом. И всем была выгодна военная мобилизация и война – заказы сыпались как из рога изобилия.

После поражения Третьего рейха в войне и до сего времени в массовом сознании людей еврейство – это жертва нацизма. Причём трагедию евреев превратили в своего рода бренд, наживаясь на ней, получая финансовые и политические дивиденды. Хотя славян в этой бойне погибло намного больше – более 30 миллионов (включая поляков, сербов и т.д.). В реальности евреи евреям рознь, одних уничтожали, преследовали, а другие евреи сами финансировал Гитлера. О вкладе влиятельных евреев того времени в становление Третьего рейха, росте влияния Гитлера «мировая общественность» предпочитает молчать. А людей, которые поднимают этот вопрос, тут же обвиняют в ревизионизме, фашизме, антисемитизме и т.д. Евреи и Гитлер – это одна из самых закрытых тем в мировых СМИ. Хотя не секрет, что фюрера и НСДАП спонсировали такие влиятельные еврейские промышленники, как Рейнольд Геснер и Фриц Мандель. Значительную помощь Гитлеру оказала знаменитая банковская династия Варбургов и лично Макс Варбург (директор гамбургского банка «М.М. Варбург & Ко»).

Среди других еврейских банкиров, которые не жалели денег на НСДАП, необходимо выделить берлинцев Оскара Вассермана (один из руководителей Deutsche Bank) и Ганса Привина. Ряд исследователей уверены, что в финансировании нацизма участвовали Ротшильды, им Гитлер был нужен для реализации проекта создания еврейского государства в Палестине. Преследования евреев в Европе вынуждали их искать новую родину, а сионисты (сторонники объединения и возрождения еврейского народа на его исторической родине) помогали в организации создании поселений на палестинских территориях. Кроме того, решалась проблема ассимиляции евреев в Европе, преследования заставляли их вспомнить о своём происхождении, объединиться, происходила мобилизация еврейского самосознания.

Интересно, что фактически Гитлера и его партию финансировали и подготовили почву для захвата нацистами власти в Германии те же силы, что готовили революции 1905, 1917 годов в России, спонсировали партию большевиков, эсеров, меньшевиков, вели плотную работу со всеми российскими революционными силами. Это так называемый «финансовый интернационал», хозяева банков США, Британии, Франции и других западных стран, американской Федеральной резервной системы.

Кроме того, надо отметить тот факт, что высшее руководство Третьего рейха само во многом состояло из евреев или людей, имеющих еврейские корни. Эти факты изложены в работе Дитриха Брондера «До прихода Гитлера», основанной на 288 источниках (он был генеральным секретарем объединения нерелигиозных общин Германии), Хенека Карделя «Адольф Гитлер — основатель Израиля» (во время войны был подполковником и кавалером рыцарского Железного креста). Немало фактов о евреях в Третьем рейхе можно найти в работах Вилли Фришауэра «Гиммлер», Уильяма Стивенсона «Братство Бормана», Джона Донована «Эйхман», Чарльза Уайтинга «Канарис» и т. д. Еврейские корни имел сам Адольф Гитлер, такие знаменитые нацисты, как Гейдрих (по отцу Зюсс), Франк, Розенберг. Евреем был один из авторов плана «Об окончательном решении еврейского вопроса» Эйхман. Уничтожением поляков и евреев на польской территории руководил еврей Ханс Михаэль Франк, он был генерал-губернатором Польши в 1939—1945 годы. Один из самых знаменитых авантюристов 20 столетия Игнац Требич-Линкольн, ярый сторонник Гитлера и его идей, родился в семье венгерских евреев.

Евреем был главный редактор антисемитской и антикоммунистической газеты «Штурмовик», идеолог расизма и ярый антисемит Юлиус Штрейхер (Абрам Гольдберг). Его казнили в 1946 году по приговору Нюрнбергского трибунала за антисемитизм и призывы к геноциду. Семитские корни имел министр пропаганды Рейха Иосиф Геббельс и его жена Магда Беренд-Фридлендер. Семитское происхождение было у Рудольфа Гесса, министра труда Роберт Лея. Есть мнение, что шеф Абвера Канарис происходил из греческих евреев.

До войны в Германии жило до полумиллиона евреев, до 300 тыс. из них свободно уехало. Частично пострадали невыехавшие, но самый большой урон понесли евреи Польши и СССР, они были значительно ассимилированы и их «пустили под нож», как утративших еврейское самосознание. Многие евреи воевали в составе вермахта, так, только в советский плен попало около 10 тыс. человек.

Лично благодаря Гитлеру появилась категория из более 150 «почетных арийцев», в которую вошли в основном крупные еврейские промышленники. Они выполняли личные поручения вождя по спонсорской поддержке тех или иных политических мероприятий. Нацисты делили евреев на богатых и всех остальных, для богачей были льготы.

Таким образом, мы видим, что усилиями западных СМИ, официальных историков, политиков из истории Второй мировой войны и её предыстории было вырезано немало интересных страниц. Евреи финансировали создание Третьего рейха, лично Гитлера, были в руководстве Германии, участвовали в «решении» еврейского вопроса, уничтожении своих соплеменников, воевали в составе немецких вооруженных сил. А после крушения Рейха на немецкий народ взвалили всю вину за геноцид еврейского народа и заставили платить контрибуцию. До сих пор Германия и немцы считаются главными виновниками разжигания Второй мировой войны, хотя организаторы этой бойни так и остались ненаказанными.

СССР и его политическое руководство любят обвинять в антисемитизме, но Сайко в книге «Перепутья на пути в Израиль» и Вейншток в работе «Сионизм против Израиля» приводят весьма интересные данные. Из евреев, которые подвергались преследованию со стороны нацистов и нашедших спасение за рубежом в период с 1935 по 1943 годы, 75% нашли убежище в тоталитарном Советском Союзе. Англия приютила около 2% (67 тыс. человек), Соединенные Штаты – менее 7% (примерно 182 тыс. человек), в Палестину уехало 8,5% беженцев.

Недавно кто то там в Европе написал статью о том, что нацисты убили не 6 миллионов евреев, а «всего то» несколько сот тысяч. И евреев в мире было до Гитлера 12-14 миллионов и в 50е годы тоже их было 12 – 14 миллионов. Значит, убили не много. И, возможно, за дело. А, следовательно, никакого геноцида не было. Его выдумали зловредные жиды для оправдания захвата чужих земель. (Дескать, никакие мы не оккупанты — от холокоста спасаемся).

Наши профессиональные антисемиты подхватили: вот ведь, опять жиды всех наебали!

Я в той дискуссии не участвовал, чтобы не опошляться. А вот сейчас решил разобрать: как там было на самом деле с геноцидом еврейского народа в Третьем рейхе?

.

Для начала сверим цифры.

Сами евреи и нацисты считали евреев по разному. И тот антисемит – автор статьи посчитал евреев по-еврейски. По синагогальным спискам прихожан. Надо ли говорить, что далеко не все евреи ходят в синагоги? А нацисты считали евреем всякого, у кого в крови было ¼ крови предка, записанного евреем. То есть, если хотя бы один из 8ми прадедушек или одна из 8ми прабабушек числились евреями, то и правнуков записывали евреем. Некоторые узнавали, что они, оказывается, евреи только по дороге в концлагерь.

.

И вот всего евреев, в том числе и таких «евреев» нацисты убили 6 миллионов.

Так что цифры в обоих случаях примерно правильные. Вопрос в том, кого считать евреем. Впрочем, в этом и сами евреи путаются, не только антисемиты. Причём, хотя тогда ещё не было генетического анализа, но нацисты пытались вычислять евреев с целью их последующего уничтожения именно генетическими методами: по записям рождений и черепа измеряли. Не по происхождению, культуре, вероисповеданию или воспитанию. Так что всё происходившее в третьем рейхе с евреями вполне подпадает под определения геноцида.

.

Позже я писал на тему сегодняшней статьи: Евреи на службе в Третьем рейхе.

Сразу скажу, что если евреи служили Гитлеру, это не значит, что геноцида не было. Да, Гитлер лично выдавал некоторым нужным евреям свидетельство того, что предъявитель сего – немец. Но эта привелегия светила только немецким евреям. И то не всем. Чаще не евреям, а «мишеленге», тоесть, полукровкам. Среди которых попадались и галахические евреи – евреи по матери. А вот негерманских евреев геноцидили по полной программе. Особенно восточно-европейских. Польских, белорусских и украинских.

.

Хотя убивали не только евреев и даже неевреев убили больше, чем евреев, но геноцид еврейского народа и был геноцидом.

Что, кстати, не отменяет факта, что современные еврейские политики и политиканы — потомки выживших в ходе геноцида евреев спекулируют на нём в своих интересах.

.

Почему евреи называют его холокостом? А потому, что ООН приняло определение «геноцид» уже сильно позже окончания войны. А по принципам ООН нельзя называть явление термином, официально введённым позже самого явления.

.

Вот тут есть статья на эту тему, которая мне показалась интересной для комментирования:

В. Герасимов. Они сражались за Гитлера. Как евреи помогали Гитлеру?

«Тысячи книг и статей посвящены еврейским страданиям в годы Второй мировой войны, поэтому о трагедии еврейского народа знают все. Эти статьи и книги миллиардными тиражами изданы на всех языках мира. Можно ли к многократно повторенным описаниям ужасов холокоста добавить что-то новое?

Автор предлагает вниманию читателей всего ОДНУ статью, которая, на наш взгляд, способна эту тему несколько расширить и обновить.

Итак, вопрос первый: всех ли евреев уничтожал Гитлер? Оказывается, далеко не всех. Возможно, это объясняется тем, что сам Адольф Алоизович был «немножко евреем». Таким же, как большинство его ближайших сподвижников. Гитлер не был евреем. Просто одна из его прабабок в 1912-1913 году не упоминалась в церковных книгах. Дескать, она могла быть и еврейкой. Но, это была эпоха наполеоновских войн и перемещений народов. Её могло занести в Австрию откуда-то извне.

Например, главный идеолог нацизма Розенберг происходил от прибалтийских евреев. Второй после фюрера человек Третьего рейха, шеф гестапо Генрих Гиммлер был полуевреем, а его первый заместитель Рейнгард Гейдрих уже еврей на 3/4. Нацистским министром пропаганды был другой типичный представитель «высшей расы», отроду хромоногий уродливый карлик с лошадиной стопой, полуеврей Иозеф Геббельс. Самым отпетым»жидоедом» при фюрере был издатель нацистской газеты «Штюрмер»Юлиус Штрейхер. После Нюрнберга издателя повесили. И на гробу написали его настоящее имя — Абрам Гольдберг, чтобы на том свете не перепутали его»девичье» имя и псевдоним. Другой нацистский преступник, Адольф Эйхман, повешенный уже в 1962 г., был чистокровным евреем из выкрестов. «Что ж, вешайте. Еще одним жидом будет меньше!» — заявил Эйхман перед казнью. А повесившийся (или повешенный) в преклоннейшем возрасте Рудольф Гесс, бывший правой рукой фюрера в руководстве нацистской партией, имел маму-еврейку.То есть по-нашему был полуевреем, а по законам иудейским — чистым евреем. Желтую «Звезду Давида» предложил пришивать к одежде евреев адмирал Канарис, шеф военной разведки. Он сам был из греческих евреев. Если командующий люфтваффе рейхсмаршал Герман Геринг был только женат на еврейке, то его первый заместитель фельдмаршал Эрхард Мильх был уже полноценным евреем. И так далее,очень напоминающее веселые картинки политического калейдоскопа в России. В этом плане интересна и поучительна история венского Ротшильда, в те времена одного из самых богатых евреев мира. Как ни в чем ни бывало, он продолжал спокойно жить в своем роскошном дворце, пока его не навестили местные штурмовики.Незваные гости вынесли из дворца немало добришка и золотишка, включая ценнейшую коллекцию старинных персидских ковров, в которой Ротшильд души не чаял.Поведение штурмовиков не на шутку рассердило банкира. И он тут же написал жалобу самому фюреру.

«Бедняга! — подумаете вы.- Его же немедленно отправят в газовую камеру!» Ошибаетесь. Гитлер принес Ротшильду извинения и возместил все убытки банкира из казны рейха. Загвоздка вышла лишь с персидскими коврами. Может быть, они очень понравились Еве Браун. Во всяком случае, по поводу унесенных ковров история умалчивает. Говорит она только о коврах принесенных.

Поясняю. Из той же государственной казны были срочно выделены средства для приобретения в Иране других антикварных персидских ковров, по художественным достоинствам и стоимости эквивалентных коврам из пропавшей коллекции. Новая коллекция была торжественно вручена безутешному миллиардеру самим Гиммлером. Он же лично руководил эвакуацией венского Ротшильда в Швейцарию.

Для этой цели Ротшильду был выделен особый железнодорожный состав с эсэсовской охраной и специальными вагонами люкс. Добро миллиардера, включая обновленную коллекцию ковров, было тщательно упаковано и погружено. Еврейская гордость не позволила Ротшильду отказаться от услуг и подарков лидеров Третьего рейха. Гиммлер лично сопровождал Ротшильда до самой швейцарской границы. Согласитесь, это мало напоминает скорбный путь в Освенцим. Но факт есть факт. Из этого фройлехса ноты не выкинешь.

Кстати: этот эпизод показывает отношение еврейской элиты к простым евреям и цену «еврейского братства». Что-то в анналах истории не отмечены усилия Ротшильда спасти евреев от газовых камер. Несмотря на авторитет его в глазах Гимлера.

Вопрос второй, не менее интересный: все ли евреи воевали против Гитлера? Ведь жертвой нацизма считает себя каждый еврей, и каждый, кто пожелал, получил за это денежную компенсацию от Германии. За грехи отцов, поверивших гитлеровским полукровкам, современные немцы расплатились и оптом, и в розницу. Ничего удивительного: проигравший всегда платит. Проблема в другом — все ли евреи имели моральное право на получение этих компенсаций? Как быть с теми евреями, которые воевали на стороне Гитлера? С теми, кто командовал фашистскими армиями, дивизиями, полками? С теми, кто разрушал русские города и деревни, убивал наших солдат, угонял в рабство русских девушек? Они что — тоже жертвы нацизма? Они никому и ничего не должны? Например: нам, детям и родственникам погибших и плененных россиян..Русская жизнь чего-то стоит? Или наши страдания заранее не в счет: подумаешь,какие-то русские!.. Впрочем, если мы сами себя не ценим, будут ли нас ценить другие?

Автор передёргивает. Из его утверждения следует, что все евреи ответственны за каждого еврея. Типа, если хотя бы один еврей – негодяй, так и все негодяи. И, следовательно, никакого геноцида не было. Геноцид, это жидовская хитрость, чтобы бабло срубить.

Но в цивилизованной юриспруденции не существует коллективной ответственности по национальному, гендерному или какому ещё принципу. Те евреи, которые убивали русских или ещё кого, пусть едут в Нюрнберг под трибунал, а те, которых убивали, здесь причём?

Либеральные авторы с удивительным постоянством забывают о том, что тысячи евреев в годы войны сражались за Гитлера. Они убивали русских, они воевали против нас. Притом убивали весьма усердно, «героически»: 20 евреев-гитлеровцев были награждены Рыцарским Крестом — высшей военной наградой нацистской Германии. В гитлеровском вермахте служили не только солдаты и младшие офицеры еврейского происхождения. 2 генерала, 8 генерал-лейтенантов, 5 генерал-майоров и 23полковника-еврея находились на самых ответственных командных должностях. Это не считая ближайших гитлеровских соратников и фельдмаршала люфтваффе Эрхарда Мильха. Никто из них прощения у нас не попросил. Мало того, не слышно даже гневных протестов со стороны самих пострадавших евреев. Гоняются по всему миру за каждым уцелевшим солдатом-полицаем, а своих маститых экс-душегубов почему-то не тревожат. Успокоились на том, что повесили самых-самых главных.

Каким образом евреи заняли столько высоких должностей в гитлеровском вермахте? Ведь существовал закон 1935г., согласно которому евреи не имели права служить в армии. Ответ дает мудрая русская поговорка: закон что дышло — куда повернул, туда и вышло. Оказывается,Гитлер лично объявил еврейских военачальников арийцами. И арийцы подчинились евреям. Так сказал фюрер, а фюрер думает за всех. Одних евреев убивать, другим евреям подчиняться. Дисциплина прежде всего. Кот лает, когда петух мяукает. .Наглядный урок юным баркашовцам, которым пора научиться думать не по писаниям психа Ницше, а своими мозгами. Добрые намерения не всегда приводят к хорошим результатам. Бездумное, слепое подчинение фюреру — удел слабых. Личность — не гвоздь, вколоченный в доску. Воля к борьбе — акт творческий.

А как там наши «герои»? Да так, живут себе потихоньку. Экс-арийцы дружно объявили себя евреями, сообща скорбят по жертвам холокоста, соучастниками которого они были сами. Они ругают фюрера. И, возможно, получают компенсации. Палачи объявили себя жертвами печальных обстоятельств. Не может быть жертвой только русский народ. Потому нам никто не должен».

Источник: Валерий ГЕРАСИМОВ, США, «Колокол» N 124/98. Дуэль N 42(89)

Третий Рейх был детищем евреев, и поэтому евреи помогали ему во всём. Мало того, что вся верхушка Рейха состояла из евреев, так и в немецкой армии служило более 150 тысяч евреев – по одному из каждой еврейской семьи Германии…

Еврейская красавица

Широкую известность получила Стелла Гольдшлаг (нем. Stella Goldschlag, в замужестве Стелла Кюблер, годы жизни 1922 — 1994 гг.). Это была красивая берлинская девушка-еврейка с «арийской» внешностью – блондинка с голубыми глазами.

После окончания школы (уже после прихода к власти нацистов) получила образование дизайнера модной одежды. Незадолго до начала войны вышла замуж за музыканта еврея Манфреда Кюблера. Работала вместе с ним на принудительных работах на фабрике в Берлине.

В 1942 году начались депортации некоторых евреев в трудовые лагеря, но она с родителями пыталась скрыться от переселения, перейдя на нелегальное положение. В начале 1943 года Стеллу выявили и арестовали. Чтобы спасти себя и своих родителей от теперь уже от неминуемой депортации, она согласилась сотрудничать с нацистами. По заданию гестапо она обследовала Берлин в поисках скрывающихся евреев, обнаружив которых, она сдавала их гестапо.

Данные о количестве её жертв колеблются между точно доказанными 600 евреев до предположительно 3000 евреев. Были также уничтожены её родители, и муж, ради которых она и согласилась на предательство. Но и после их смерти красотка продолжала сдавать евреев нацистам. Зато она смогла спасти несколько своих бывших одноклассников и знакомых. И, конечно, себя, любимую…

По окончании войны попыталась скрыться. Родила дочь, которая жива до настоящего времени, носит имя Ивонна Майсль и крайне отрицательно относится к своей матери. Стелла Кюблер была арестована советскими спецслужбами в октябре 1945 года и приговорена к 10 годам заключения. После этого вернулась в Западный Берлин, где также была приговорена к 10-летнему сроку, однако не отбывала его ввиду ранее отбытого наказания. Характерно, что Стелла повторно вышла замуж за бывшего нациста. В возрасте 72 лет совершила самоубийство.

Евреи — агенты гестапо

В 1955 г., до своего ареста, свободный Эйхман дал интервью голландскому журналисту, в котором он так характеризовал свои отношения с Кацнером:

«Этот д-р Кастнер был молодым человеком примерно моего возраста, холодный как лёд юрист и фанатичный сионист. Он согласился помочь удерживать евреев от сопротивления депортации и даже поддерживать порядок в лагерях, где они были собраны, если я закрою глаза и позволю нескольким сотням или даже тысячам молодых евреев нелегально эмигрировать в Палестину. Это была хорошая сделка. Для поддержания порядка в лагерях освобождение 15, даже 20 тысяч евреев – в конечном счёте их могло быть и больше – не казалось мне слишком высокой ценой. После нескольких первых встреч Кацнер никогда не выказывал страха передо мною – сильным человеком из Гестапо. Мы вели переговоры абсолютно на равных… Мы были политические оппоненты, пытавшиеся прийти к соглашению, и мы абсолютно доверяли друг другу. Сидя у меня, Кастнер курил сигареты… одну за другой. С его прекрасным лоском и сдержанностью он сам мог бы быть идеальным гестаповским офицером».

В послевоенные годы Кацнер проявил просто-таки удивительную заботу как минимум о 4-х высших офицерах СС, один из которых, Курт Бехер благодаря его показаниям был оправдан на суде в Нюрнберге. С этим Бехером связана темная история: в первые послевоенные дни он с помощью 3-х евреев пытается передать Сохнуту и Джойнту полученные от Кацнера за поезд 2 миллиона долларов для использования их на благо еврейского народа (его собственные слова). Прежде чем попасть по адресу, чемоданы с деньгами попадают в руки американской контразведки. Еврейским организациям в итоге достается только 50 тысяч долларов. Остается лишь гадать: либо Бехер «недоложил» весьма существенную сумму, либо американцы «облегчили» чемоданы, либо это сделали евреи-носильщики. Интересно, что Гиммлер поручил полковнику Бехеру присутствовать при всех встречах чистокровных евреев Эйхмана и Кацнера.

В 1957 году Кацнер был убит в Тель-Авиве группой «чудом переживших холокост» венгерских евреев.

Ещё был организатор пражской «ярмарки еврейских душ» Роберт Мандлер — представитель Еврейского агентства в бывшей Чехословакии и по совместительству агент командующего чехословацкого отделения Гестапо Фоша. Мандлер по договоренности с немцами вывез из Чехословакии сотни сионистских функционеров и финансовых тузов. Однажды вместе с выкупленными у нацистов богачами и сионистскими активистами на борту «Патрии» в Палестину была отправлена группа молодых евреев из Чехословакии. Когда пароход уже находился в открытом море, сионистские эмиссары пронюхали, что некоторые из парней вовсе не собираются пополнять ряды так называемых «халуцов» — молодых колонизаторов Палестины и не хотят с оружием в руках сгонять палестинцев с их родных мест. Они намеревались войти в ряды формировавшегося на Ближнем Востоке отряда чехословацкой молодежи, который намеревался тайком вернуться в Европу и влиться в освободительную армию генерала Свободы. Об «изменниках» было сообщено сионистскому центру в Палестине, приказавшему изолировать их от остальных пассажиров. Это трудно себе представить, но для сионистов участие чехословацких евреев в вооруженной борьбе с гитлеровскими оккупантами являлось недопустимым нарушением заключенных с нацистами сделок.

Согласно показаниям одного из высших офицеров СС Карла Дама, нацисты сформировали из сионистов еврейскую полицию для поддержания порядка в концлагере «Teriseen» в Чехословакии. Карл Дам добавил, что благодаря помощи сионистских агентов, в период с 1941 по 1945 годы им удалось определить более 400.000 евреев Чехословакии в гетто и исправительно-трудовые лагеря.

Немецкий писатель Юлиус Мадир подтвердил, что существует длинный список сионистских лидеров, активно сотрудничавших с нацистами. Их имена занимают 16 страниц. Среди них находятся имена высших официальных лиц Израиля. Например, Хаим Вейцман, Моше Шарет, Давид Бен-Гурион, Ицхак Шамир и другие. Самыми важными нацистскими друзьями сионистов были Курт Бехер и Адольф Эйхман — 100-процентный еврей, хотя по документам он проходил как австриец. Его соратники по СС удивлялись, что к ним попал этот человек с ярко выраженным семитским носом. «У него посреди рожи торчит ключ от синагоги» — говорили они. «Молчать! Приказ фюрера!» — обрывали их.

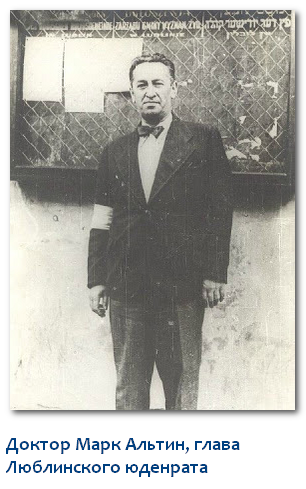

Помимо широко известного Резо (он же Рудольф а впоследствии Исраэль) Кацнера — заместителя председателя еврейского агенства в Венгрии, помогавшего нацистам депортировать венгерских евреев в трудовые лагеря, и Файфеля Полкеса — руководителя военной организации сионистов «Хаганы» и одновременно агента гестапо в Палестине были еще и Адольф Ротфельд — председатель Львовского юденрата руководивший сначала депортацией местных евреев в гетто а затем и их переправкой в трудовые лагеря; Макс Голигер — шеф так называемой «еврейской службы порядка» во Львове и по совместительству агент немецкой полиции безопасности, охотившийся на львовских евреев как на зверей; Шама Штерн — председатель юденрата в Будапеште, председатели юденратов в Голландии Вайнреб и Вайнштейн, Манфред Райфер — в Черновцах, Леопольд Гере в Чехословакии. Список можно продолжать бесконечно.

Этих перечисленных выше нацистских пособников объединяло и то, что все они занимали видные посты в сионистской иерархии. Так например, упомянутый выше председатель Львовского юденрата Адольф Ротфельд, по совместительству занимал пост вице-президента краевого совета сионистских обществ, являясь одновременно членом секретариата колониального фонда «Керен Хаесод». Леопольд Гере являлся директором пражского «Переселенческого фонда евреев» (подобно другому старейшему польскому сионисту, председателю аналогичного фонда в Варшаве и агенту гестапо Носсигу, казненному узниками Варшавского гетто, Гере делил с нацистами имущество убитых евреев). Председатель юденрата в Черновцах Манфред Райфер возглавлял сионистскую организацию Буковины и по совместительству руководил еврейским агентством в области (Райфер прославился хвалебными статьями о третьем Рейхе и его фюрере в начале 30-х годов). Макс Голигер до своего назначения в качестве начальника так называемой «еврейской службы порядка» в Галиции возглавлял местную молодежную сионистскую организацию.

Если перечислять всех сионистских пособников нацизма, то список получится весьма длинным. Особенно если включить в него всех тех, кто через издававшиеся в еврейских гетто газетах призывал своих собратьев к покорности и сотрудничеству с нацистами, и тех, кто в составе так называемой еврейской полиции помогал нацистам отлавливать и депортировать в трудовые лагеря десятки и сотни тысяч евреев.

К слову, все издававшиеся в гетто газеты принадлежали до войны местным сионистским организациям. В большинстве случаев, нацисты не только сохранили эти газеты но и расширили их штат.

Евреи – агенты абвера

Разведывательное ведомство адмирала Канариса — абвер — «кишел евреями, в том числе и чистокровными» (Л. Фараго. «Игра лис». Нью-Йорк, 1971 г.). С июня 1941 года агентом под номером А.2408 стал барон Вольдемар Оппенгейм. Особую известность в нацистском шпионском ведомстве снискал венгерский еврей Эндрю Джорджи, помогавший Эйхману обменивать евреев на необходимые рейху товары. В 50-е годы, отсидев несколько лет за сотрудничество с «наци», он сменил фамилию и превратился в преуспевающего бизнесмена. (Амос Илан. «История Джоэля Бранда». Лондон, 1981 г.). Одной из самых выдающихся немецких секретных агентов-женщин во время Второй мировой войны была Вера Шальбург (Vera Schalburg), которая родилась в 1914 году в Киеве в еврейской семье. Вера работала танцовщицей в ночном клубе Парижа, затем перебралась в Гамбург, где стала любовницей высокопоставленного сотрудника абвера Диркса Хилмара. Диркс принял ее на службу в абвер, где она зарекомендовала себя как лучший германский разведчик-женщина. В сентябре 1940 года Вера и двое других агентов высадились на побережье Шотландии, но вскоре все они были арестованы. Ее спутников повесили как шпионов, а Вера исчезла. Предполагается, что ее перевербовали англичане — личное дело Веры Шальбург в военной разведке (MI5) до сих пор засекречено.

Евреи в германских вооружённых силах

Это звучит неестественно и неправдоподобно, но историческая правда в том, что 150 тысяч солдат с прожидью состояли на службе в гитлеровской армии (Шимон Бриман, «Еврейские солдаты Гитлера»). Евреи только по отцу или только по матери и не исповедающие иудаизм, в Германии евреями не считались — они были т.н. «мишлинге».

Десятки тысяч таких «мишлинге» преспокойно жили в нацистской Германии. Они призывались на службу в Верхмат и в Люфтваффе в самом обычном порядке. В январе 1944 года кадровый отдел Вермахта составил список 77 высокопоставленных офицеров и генералов, «смешанных с еврейской расой или женатых на еврейках». Среди них — 23 полковника, 5 генерал-майоров, 8 генерал-лейтенантов и 2 полных генерала армии. К этому списку можно добавить еще 60 фамилий высших офицеров и генералов Вермахта, авиации и флота, включая 2 фельдмаршалов. Считается, что во всей верхушке Третьего Рейха лишь Геринг не имел примесей еврейской крови. Сотни «мишлинге» были награждены за храбрость Железными крестами. 20 солдат и офицеров еврейского происхождения были удостоены высшей военной награды Третьего Рейха — Рыцарского креста.

Среди евреев, занимавших высокое положение в нацистской Германии, первое место, безусловно, принадлежит фельдмаршалу Эдварду Мильху — второму человеку в Люфтваффе после Германа Геринга. Когда к «толстому Герману» примчались взволнованные гестаповцы с «криминалом» на его заместителя, рейхс-маршал заорал на них и произнес фразу, ставшую крылатой: «Я решаю, кого считать евреем!» Мильха в срочном порядке произвели в «почетного арийца». Процесс «арианизации» иногда проходил исключительно быстро. Гестаповцы, пронюхавшие, что фрейлейн Кунде — повариха, присланная фюреру румынским маршалом Антонеску, — еврейка, немедленно доложили об этом «шефу». Нисколько не смутившись, Гитлер ответил им: «Ну и что? Зачем беспокоить меня по пустякам? Неужели сами не можете сообразить, что надо делать? Арианизируйте ее!» (Алан Абрамс. «Специальное обращение». Нью-Джерси, 1985 г.).

Молодой 30-летний американский еврей Брайан Марк Бригг в одиночку задокументировал 1200 примеров службы «мишлинге» (солдат и офицеров) в вермахте. У тысячи из этих фронтовиков были депортированы 2300 еврейских родственников. Вот уж парадокс: дети и внуки интернированных евреев воюют на стороне Гитлера. И после войны они могли бы спокойно уехать в Израиль. В соответствии с израильским законом о возвращении.

«Сколько же евреев сотрудничало с нацистами?» — вопрошает уже упоминавшийся Брайан Бригг, покопавшийся в архивах и ужаснувшийся от того, что «сотни офицеров еврейского происхождения получили очень высокие награды за героизм в нацистской армии». Вряд ли Бриггу удастся получить точный ответ на свой вопрос.

26 октября 1949 года советскими органами был арестован некий Гутгари Шмиль Григорьевич, 1920 года рождения, беспартийный.

В советских документах о нём было написано так:

«Обвиняется в измене родине. Находясь на фронте Отечественной войны, в 1941 году уничтожил комсомольский билет, бросил оружие и перешел к немцам.

Находясь в лагере военнопленных в гор. Бяла-Подляска (Польша), выдал себя за «фольксдойч», после чего был направлен в учебный лагерь «СС» в Травники. В течение трех лет служил адъютантом и переводчиком немецкого языка при коменданте лагеря, принимал активное участие в массовом истреблении мирных граждан и зверски избивал заключенных. В сентябре 1944 года с приближением советских войск, бежал на Запад».

Лагерь СС «Травники» – это место, где обучались коллаборационисты из числа военнопленных, добровольцев, а также немцы-фольксдойче с оккупированных территорий Восточной Европы. Эти люди обучались для охраны концентрационных лагерей. Судя по воспоминаниям, были очень жестокими. Очевидно, знание немецкого языка очень пригодилось Гутгари для общения немецкого начальства и курсантов с советских территорий.

Евреи-капо

В послевоенном Израиле еврей, чтобы нанести оскорбление другому еврею, обзывал его самым непотребным словом «капо». Капо – это привилегированный заключённый в концлагерях фашистской Германии, работавший на администрацию и следящий за повседневной жизнью простых заключенных. Капо выполнял функции надзирателя. По иерархии находившаяся ниже «оберкапо», но выше «бригадиров» (старшие рабочих групп).

В капо заключённые шли, естественно, не из-за идейных соображений, а исключительно ради улучшения своего существования. Актив капо пополнялся в основном за счёт евреев, уголовников, реже — лагерных ветеранов. Нередко среди капо были гомосексуалисты, а также коммунисты (как правило евреи), перемещенные с оккупированных территорий и старающиеся выйти из рамок самой нижней ступени лагерной иерархической лестницы. Из-за сотрудничества с нацистской администрацией, капо не пользовались особым уважением, но имели власть над простыми заключенными.

Привилегии позволяли капо существовать более-менее нормально: они жили в централизовано отапливаемых помещениях, получали усиленное питание (в том числе благодаря возможности распределять выделяемые для всех узников продукты в свою пользу), пользовались гражданской одеждой и хорошей обувью. В обмен на эти послабления режима нацистское руководство концлагерей ожидало от капо жестоких и эффективных действий в отношении простых заключенных, поддержания жесточайшей дисциплины, выполнения рабочих норм при помощи запугивания и избиений. Актив, как правило, был настолько же жесток к простым заключенным, как и нацистская охрана концлагерей. Капо-евреи очень боялись, что за недостаточное рвение их могут перевести обратно в простые заключённые и потому не знали жалости не только к гоям, но и к своим единоверцам. В качестве оружия у них были дубинки.

Власть над людьми евреи-капо могли использовать ради своих скудных утех.

Штефан Росс, основатель музея холокоста в Новой Англии (регион США), утверждает, что 20 процентов евреев-капо были гомосексуалы. Сам Росс пять лет был в заключении в нацистских лагерях, и ребенком испытал сексуальное домогательство со стороны еврейских охранников. Они били его, заставляя исполнять с ними оральный секс. Возможно, некоторые капо до концлагеря не были гомосексуалистами-педофилами, но жизнь без женщин, лёгкая возможность воспользоваться такими сексуальными услугами, а также лагерная атмосфера сделали из них таких существ.

Иногда руководство лагерей ставило капо-евреев над заключёнными немцами. Этим нацисты пытались унизить немецких заключённых, мол, вы настолько ничтожны, что вами командуют евреи.

По воспоминаниям немца-коммуниста Бернхарда Кандта, в прошлом депутата мекленбургского ландтага, а позднее попавшего в Заксельхаузен о работе SAW-арестантов:

«Мы должны были нанести на лесную почву шесть метров песка. Лес не был вырублен, что должна была сделать специальная армейская команда. Там были сосны, как я сейчас вспоминаю, которым было дет по 100-120. Ни одна из них не была выкорчевана. Заключённым не давали топоров. Один из мальчишек должен был забраться на самый верх, привязать длинный канат, а внизу двести мужчин должны были тянуть его. «Взяли! Взяли! Взяли!». Глядя на них, приходила мысль о строительстве египетских пирамид. Надсмотрщиками (капо) у этих бывших служащих вермахта были два еврея: Вольф и Лахманн. Из корней выкорчеванных сосен они вырубили две дубины и по очереди лупцевали этого мальчишку… Так сквозь издевательства, без лопат и топоров они выкорчевали вместе с корнями все сосны!».

По воспоминаниям, заключённые после этого ненавидели всю еврейскую нацию…

Пропагандист холокоста Эли Визель с гордостью отмечает:

«в лагерях были евреи капо родом из Германии, Венгрии, Чехии, Словакии, Грузии, Украины, Франции и Литвы. Среди них были христиане, евреи и атеисты. Бывшие профессора, промышленники, художники, торговцы, рабочие, политики и правые, и левые, философы и исследователи человеческих душ, марксисты и последователи гуманистов. И конечно, попадались и просто уголовники. Но ни один капо не был прежде раввином».

Даже когда намечалось скорое освобождение союзниками, большинство евреев-капо лучше относиться к своим не стало. Даже страх быть казнённым из-за сотрудничества с нацистами не пугал таких капо. По воспоминаниям Исраэля Каплана, в конце войны немцы гнали евреев из концлагерей в глубь Германии. Сам Каплан был в колонне, которая совершала «марш на Тироль» и попал в концлагерь Аллах — внешний лагерь Дахау, где до этого евреев не было вообще (концлагерь считался «нееврейским»).

В апреле 1945 года часть евреев была отправлена дальше, а примерно 400 евреев осталась в Аллахе (в основном это были выходцы из Венгрии и немного из Польши). К пятнице 27 апреля количество евреев достигло 2300 человек.

С крахом Германии система отношения к евреем стала изменяться – эсэсовцы перестали заходить в еврейскую часть лагеря, ограничили свою деятельность внешней охраной, а управляли через своих верных помощников – еврейских старост, капо и др. Капо еврейской части лагеря также перестали заходить в общие блоки, заполненные больными и умирающими узниками. У охранников из СС возникла новая проблема — как избежать наказания, сбежать, раствориться.

Евреев было очень много, а бараков всего 5 штук. Теснота в блоках была страшной, больные лежали рядом со здоровыми и заражали их, при этом измождённость людей делала их иммунную систему настолько слабой, что они быстро умирали. Тут проявилась сущность некоторых узников евреев – предчувствуя скорое освобождение, они старались дожить до него даже за счёт смерти своих же солагерников. В большинстве это были люди, уже запятнавшие себя сотрудничеством с нацистами.

Поэтому чтобы выжить, евреи-коллаборационисты, как наиболее здоровые и сильные, захватили один барак только для себя. Их было 150 евреев-капо, лагерных писарей, старост и других немецких прислужников. Второй барак прихватили еврейские врачи из Венгрии, где под видом больных они держали своих протеже. Три оставшихся барака вмещали «простых» евреев — 2000 человек при общей вместимости 600 человек. Судя по воспоминаниям, у живых не было сил выкинуть на улицу трупы…

Но и в этой страшной ситуации среди евреев оказались люди, готовые ради собственного спасения идти на всякие подлости: группа шустрых еврейских узников, прибывших из разных стран и лагерей, быстро сговорилась и объявила себя «полицией еврейских блоков». Но вместо оказания помощи и наведения порядка среди больных, изоляции умерших они отделили себе часть одного из трёх бараков, вышвырнув больных с нар, и устроили себе просторную площадку. Потом взяли на себя право распределять пищу и, естественно, себе брали больше. На этом их функции и кончились. Однако после освобождения, утром 30 апреля, они объявили себя главными и важнейшими представителями еврейских узников.

Реальные факты свидетельствуют о подпольщиках среди капо в трудовом лагере Треблинка. Там во главе подпольной организации стояли врач эсэсовского персонала Ю. Хоронжицкий и главный капо инженер Галевский, в секторе уничтожения подпольщиками руководил бывший офицер чехословацкой армии З.Блох. Среди руководства были и другие евреи-капо и старшие рабочих групп.

Кроме собственно надсмотрщиков, заключённые-евреи сплошь и рядом были различными полезными прислужниками и помощниками для нацистов. Потерять своё вакантное место они боялись также, как и капо.

Были простые подсобники, собирающие трупы, а также квалифицированные плотники, каменщики, пекари, портные, парикмахеры, врачи, подсобные рабочие и т. д., для обслуживания лагерного персонала и др. Были евреи и в команде известного врача Менгеле.

Нацисты награждают евреев медалями

В годы Второй Мировой войны несколько евреев были награждены немецкими наградами…

Размещение «фальшивомонетного двора» было избрано в блоке 19 концлагеря Ораниенбург – подальше от посторонних глаз, кроме того, здесь было легко ликвидировать ставшего ненужным специалиста. Заключённые-спецы были рады своей новой работе, особенно евреи — теперь они не боялись за свою жизнь, по крайней мере, пока проходила операция «Бернхард». Характерно, что остальные заключённые концлагеря относились крайне враждебно к «счастливчикам».

У тех был особый режим, отдых, хорошее питание, они ходили в гражданской одежде. После войны эти специалисты разных национальностей признавались, что отношение к ним было весьма доброжелательным, и они сами стремились повышать выпуск своей фальшивой продукции. Интересно, что лучшим фальшивомонетчиком был не еврей, а болгарский цыган Соли Смолянов.

Наконец, в 1943 году было решено наградить специалистов наградами – 12 медалей «За военные заслуги» и 6 орденов «За боевые заслуги II степени» (так в переводе. По мнению автора статьи, имеются в виду медали креста «За военные заслуги» (ими награждались только гражданские лица) и т.н. «Военные ордена Германского креста»). Подпись о награждении получили у самого Кальтенбруннера, правда, как потом оказалось, в списке было три еврея. Тем не менее, «герои» получили свои награды, в том числе и евреи, и коменданта концлагеря во время очередного обхода чуть не хватил инсульт. После этого инцидента было разбирательство, в ходе которого, как оказалось, Кальтенбруннер подписал бумагу о награждении, не читая её! Тем не менее, дело было «спущено на тормозах», никто наказан не был, заключённым было всего лишь запрещено показываться со своими наградами за пределами своего барака. Все заключённые барака пережили крушение Третьего Рейха, т.к. операция проводилась до самого конца войны, и остались живы.

«Юденраты» и еврейские полицейские

По ходу оккупации немцы создавали на территориях Польши и СССР т.н. гетто (еврейские кварталы) — закрытые еврейские районы в больших городах. Для управления внутренней жизнью гетто создавался административный орган, состоящий из влиятельных евреев, в том числе раввинов. Этот орган назывался «юденрат» (нем. Judenrat — «еврейский совет»). Таким образом на оккупированных немцами территориях было создано около 1000 юденратов (из них около 300 в Украине).

Сотрудники юденрата гетто Лодзь (в центре Дора Фукс, слева от нее Соломон Сер).

В полномочия юденрата входила регистрация евреев, обеспечение хозяйственной жизни и порядка в гетто, сбор денежных средств, распределение провизии, отбор кандидатов для работы в трудовых лагерях, а также выполнение распоряжений оккупационной власти.

Характерно, что члены юденрата несли личную ответственность перед немецкими гражданскими или военными властями. В СССР глава юденрата назывался «старостой».

Членами юденрата назначались авторитетные евреи. Так, военные власти в Прибалтике, Западной Украине и Белоруссии привлекали для этого руководителей еврейской общины, известных адвокатов, врачей, директоров и преподавателей школ. В юденрат Львова входили три адвоката, два торговца и по одному — врач, инженер и ремесленник. В Злочеве (Галиция) членами «юденрата» стали 12 человек со степенью доктора наук. Немцы до войны хотели переселить евреев на окраины своей империи. В тоже время члены юденрата прекрасно осознавали, что придётся пожертвовать внушительной частью «неполезных» немцам евреев. Надеясь на скорое создание еврейского государства и опираясь на порядочность нацистов, они призывали подчиняться немцам, выявляли еврейских преступников, боевиков и бандитов.

Для поддержания порядка и для помощи юденратам в гетто создавалась еврейская полиция (пол. Żydowska Służba Porządkowa или «жидовская служба порядка»). Полицейские обеспечивали внутренний правопорядок в еврейских гетто, участвовали в облавах на нелегальных евреев, осуществляли конвоирование при переселении и депортации евреев, обеспечивали выполнение приказов оккупационных властей и т. д.

В крупнейшем Варшавском гетто еврейская полиция насчитывала около 2500 (на примерно 0,5 млн. человек); в Лодзь до 1200; во Львове — до 750 человек, Вильнюсе 210, Кракове 150, Ковно 200. Кроме территорий СССР и Польши еврейская полиция существовала в Берлине, концлагере Дранси во Франции и концлагере Вестерброк в Голландии.

Еврейская полиция в своем большинстве состояла из членов сионистских военизированных и молодежных организаций. Так например, подручные вышеупомянутого Голлигера из «еврейской службы порядка» практически поголовно были членами молодежной сионистской организации Галиции.

Как уже говорилось, коллаборационисты, служащие в юденратах и полиции, по идее, имели возможность устраивать саботаж, скрывать членов движения сопротивления, спасать своих единоверцев, осуществлять шпионаж и всячески бороться против немцев. Однако, как показали реалии жизни, лишь единицы людей, имеющих такую ограниченную власть, пытались облегчить судьбу евреев…

Самое известное гетто, испытавшее и бандитский бунт и полную ликвидацию, было в Варшаве. В нём были все типы еврейских коллаборационистов – члены юденрата, полицейские и многочисленные агенты гестапо.

У израильского истеблишмента есть очень веские основания для того чтобы скрывать правду о преступлениях юденратов, потому что в подавляющем большинстве своем эти нацистские пособники являлись сионистскими функционерами. Судья Беджамин Халеви, который судил в Израиле и Кацнера и Эйхмана, узнал от Эйхмана на перекрёстном допросе, что нацисты рассматривали сотрудничество юденратов с нацистами как основу, фундамент еврейской политики. Где только евреи ни жили, у них везде были признанные еврейские вожди, которые почти без исключения так или иначе сотрудничали с нацистами. Продолжение тут

ЕВРЕИ НА СЛУЖБЕ ВЕРМАХТА ТРЕТЬЕГО РЕЙХА

Терминология

Вермахт – вооруженные силы Германии (1935-1945), состоящие из сухопутных войск, военно-морского флота (кригсмарине) и военно-воздушных сил (люфтваффе).

ООН – Организация Объединенных Наций создана 26 июня 1945 года. СССР вступил в ООН 24 октября 1945 года.

Третий рейх – «Третья империя» — неофициальное название Германского государства – Deutsches Reich (1933-1943), Groβdeutsches Reich (1943-1945).

«Вся реальная история Второй мировой войны умышленно закрыта и фальсифицирована. До настоящего времени о Гитлере и нацизме никакой объективной информации в России практически нет. Евреи были союзниками и активными деятелями гитлеровской Германии повлиявшими на ход и результат войны…

Либеральные авторы с удивительным постоянством забывают о том, что тысячи евреев в годы войны сражались за Гитлера. Они убивали русских, они воевали против нас. При том, убивали весьма усердно… Никто из них прощения у нас не попросил» и никогда не попросит (16).

150 тысяч солдат и офицеров вермахта могли бы репатриироваться в Израиль согласно Закону о возвращении, но они избрали для себя, абсолютно добровольно, служение фюреру (3, 5, 10, 34).

Абсолютное большинство евреев – ветеранов вермахта говорят, что идя в армию, они не считали себя евреями (5, 34).

Очень подробно о службе евреев в вермахте Третьего рейха написал в своём исследовании Брайен Марк Ригг «Еврейские солдаты Гитлера: нерассказанная история нацистских расовых законов и людей еврейского происхождения в германской армии» (2002 г.).

Брайен Марк Ригг (род. 1971) – американский историк, профессор Американского военного университета, доктор философии. Родился в Техасе в семье христиан-баптистов. Служил в качестве офицера в Корпусе морской пехоты США. Окончил с отличием исторический факультет Йельского университета, получил грант от Фонда Чарльза и Джулии Генри для продолжения обучения в Кембриджском университете в Великобритании. Обнаружив, что его бабушка была еврейкой, постепенно стал приближаться к иудаизму. Учился в иерусалимской иешиве «Ор Самеах». Служил добровольцем во вспомогательных частях Армии обороны Израиля.

Подсчёты и выводы Ригга звучат достаточно сенсационно: в германской армии, на фронтах Второй мировой, воевало до 150 тысяч солдат, имевших еврейских родителей или бабушек с дедушками.

Термином «мишлинге» в рейхе называли людей, родившихся от смешанных браков арийцев с неарийцами.

Мишлинге (Mischlinge) – «смешанные», нечистокровные евреи. Евреями назывались люди, по крайней мере, с тремя чисто еврейскими бабушками или дедушками.

Мишлингом первой степени, или полуевреем, назывался человек с двумя еврейскими дедушками или бабушками, не исповедовавший иудаизм и не состоявший в браке с евреем или еврейкой.

Мишлингом второй степени, евреем на четверть, назывался человек с одним еврейским дедушкой или одной еврейской бабушкой, или же ариец, состоящий в браке с евреем или еврейкой. В 1939 году в Германии находилось 72 000 мишлинге первой степени и 39 000 мишлинге второй степени.

Несмотря на юридическую «подпорченность» людей с еврейскими генами и, невзирая на трескучую пропаганду, десятки тысяч «мишлинге» преспокойно жили при нацистах: «не были депортированы или стерилизованы и не стали объектом истребления. На основании ранее принятых законов они были отнесены к категории неарийцев, и большинство из них уцелело» (5).

Они обычным порядком призывались в вермахт, люфтваффе и кригсмарине, становясь не только солдатами, но и частью генералитета, на уровне командующих полками, дивизиями и армиями.

В январе 1944 года кадровый отдел вермахта подготовил секретный список 77 высокопоставленных офицеров и генералов, «смешанных с еврейской расой или женатых на еврейках». Все 77 имели личные удостоверения Гитлера о «немецкой крови». Среди перечисленных в списке – 23 полковника, 5 генерал-майоров, 8 генерал-лейтенантов, два полных генерала армии, один генерал-фельдмаршал (40).

Так, подполковник Абвера Эрнст Блох – сын еврея получил от Гитлера следующий документ: «Я, Адольф Гитлер, фюрер немецкой нации, настоящим подтверждаю, что Эрнст Блох является особой немецкой крови»…

Сегодня Брайан Ригг заявляет: «К этому списку можно добавить еще 60 фамилий высших офицеров и генералов вермахта, авиации и флота, включая двух фельдмаршалов»…(там же).

Вот одни из них –

Ханс Михаэль Франк – личный адвокат Гитлера, генерал-губернатор Польши, рейхсляйтер НСДАП, полуеврей.

Бывший канцлер ФРГ Гельмут Шмидт, офицер люфтваффе и внук еврея, свидетельствует: «Только в моей авиачасти было 15-20 таких же парней, как и я. Убежден, что глубокое погружение Ригга в проблематику немецких солдат еврейского происхождения откроет новые перспективы в изучении военной истории Германии XX века».

Сотни «мишлинге» были награждены за храбрость Железными крестами.Двадцать солдат и офицеров еврейского происхождения были удостоены высшей военной награды Третьего рейха – Рыцарского креста (там же).

Рыцарский крест, первая степень ордена Железного креста в Третьем рейхе, учрежден по приказу Адольфа Гитлера в 1939 году.

«Например, главный идеолог нацизма Розенберг происходил от прибалтийких евреев. Второй после фюрера человек Третьего рейха, шеф гестапо Генрих Гиммлер был полуевреем, а его первый заместитель Рейнгард Гейдрих уже еврей на 3/4. Нацистским министром пропаганды был другой типичный представитель «высшей расы», отроду хромоногий уродливый карлик с лошадиной стопой, полуеврей Йозеф Геббельс.

Самым отпетым «жидоедом» при фюрере был издатель нацистской газеты «Штюрмер» Юлиус Штрейхер. После Нюрнберга издателя повесили. И на гробу написали его настоящее имя – Абрам Гольдберг, чтобы на том свете не перепутали его «девичье» имя и псевдоним.

Другой нацистский преступник, Адольф Эйхман, повешенный уже в 1962 году, был чистокровным евреем из выкрестов. «Что ж, вешайте. Еще одним жидом будет меньше!» — заявил Эйхман перед казнью. А повесившийся (или повешенный) в преклоннейшем возрасте Рудольф Гесс, бывший правой рукой фюрера в руководстве нацистской партией, имел маму – еврейку. То есть по-нашему был полуевреем, а по законам иудейским – чистым евреем.

Желтую «Звезду Давида» предложил пришивать к одежде евреев адмиралКанарис, шеф военной разведки. Он сам был из греческих евреев. Если командующий люфтваффе рейхсмаршал Герман Геринг был только женат на еврейке, то его первый заместитекль фельдмаршал Эрхард Мильх был ужеполноценным евреем» (16).

Ниже мы приводим ключевые фигуры Третьего рейха, имеющие связь с еврейством плоть от плоти и кровь от крови.

Гитлер (Hitler) (настоящая фамилия Шикльгрубер) Адольф (1889-1945), главный немецко-фашистский военный преступник, австрийский еврей.

Установил в Германии режим фашистского террора. С 1938 верховный главнокомандующий вооруженными силами. Непосредственный инициатор развязывания Второй мировой войны 1939-1945 г.г., вероломного нападения на СССР 22 июня 1941 года. Один из главных организаторов массового истребления военнопленных и мирного населения на оккупированных территориях (16, 25, 39).

Фюрер Германии (1934-1945), рейхсканцлер Германии (1933-1945), председатель НСДАП (1921-1945). Отец – Алоис Шикльгрубер (1837-1903), сын – банкира – еврея, мать – Клара Пёльтцль (1860-1907).

Альфред Розенберг (1893-1946) – главный идеолог нацизма, рейхсляйтер (высший партийный функционер, ранг присваивал лично Гитлер), руководитель внешнеполитического управления национал-социалистической немецкой рабочей партии (с 1933 г.), Уполномоченный фюрера по контролю за общим духовным и мировоззренческим воспитанием НСДАП, рейхсминистр восточных оккупированных территорий (с 17 июля 1941 г.).

Генрих Гиммлер (1900-1945) – Рейхсфюрер СС (1929-1945), рейхсминистр внутренних дел Германии (1943-1945), рейхсляйтер (1933-1945), и.о. начальника Главного управления имперской безопасности (РСХА) (1942-1943), статс-секретарь Имперского министерства внутренних дел и шеф германской полиции (1936-1943).

И.о. начальника РСХА Гиммлер стал после убийства еврея Рейнхарда Гейндриха.

Рейнхард Гейдрих (1904-1942) – и.о. рейхспротектора Богемии и Моравии (1941-1942), начальник Главного управления имперской безопасности (РСХА) (1939-1942), начальник тайной государственной полиции Третьего рейха (Гестапо) (1934-1939), президент международной организации уголовной полиции (Интерпола) (1940-1942), обергруппенфюрер СС и генерал полиции, отец Бруно Зюсс – еврей.

Адольф Эйхман (1906-1962) – непосредственно ответственный за массовое уничтожение евреев, начальник отдела IVВ4 Гестапо РСХА (1939-1941), начальник сектора IVВ4 Управления IV РСХА (1941-1945), оберштурмбаннфюрер СС.

Рудольф Гесс (1894-1987) – заместитель фюрера по партии (1933-1941), рейхсминистр (1933-1941), рейхсляйтер (1933-1941). Обергруппенфюрер СС и обергруппенфюрер СА (штурмовые отряды НСДАП).

Вильгельм Канарис (1887-1945) – начальник службы военной разведки и контрразведки (Абвера) (1935-1944), адмирал.

Эрхард Мильх (1892-1971) – немецкий военный деятель, заместитель Геринга, рейхсминистра авиации Третьего рейха, генеральный инспектор люфтваффе, генерал-фельдмаршал (1940).

Американским военным трибуналом объявлен военным преступником. В 1947 году его судили и приговорили к пожизненному заключению. В 1951 году срок сократили до 15 лет, а к 1955 году досрочно освободили.

Вернер Гольдберг. Долгое время нацистская пресса помещала на своих обложках фотографию голубоглазого блондина в каске. Под снимком значилось: «Идеальный немецкий солдат». Этим арийским идеалом был боец вермахта еврей Вернер Гольдберг.

Вальтер Холландер. Полковник Вальтер Холландер, чья мать была еврейкой, получил личную грамоту Гитлера, в которой фюрер удостоверял арийство этого галахического еврея. Такие же удостоверения о «немецкой крови» были подписаны Гитлером для десятков высокопоставленных офицеров еврейского происхождения.

Холландер в годы войны был награжден Железными крестами обеих степеней и редким знаком отличия – Золотым Немецким крестом. Холландер получил Рыцарский крест в июле 1943 года, когда его противотанковая бригада в одном бою уничтожила 21 советский танк на Курской дуге. Умер в 1972 году в ФРГ.

Роберт Борхардт. Майор вермахта Роберт Борхардт получил Рыцарский крест за танковый прорыв русского фронта в августе 1941 года. Затем Борхардт был направлен в Африканский корпус Роммеля. Под Эль-Аламейном Борхардт попал в плен к англичанам. В 1944 году военнопленному разрешили приехать в Англию для воссоединения с отцом-евреем. В 1946-м Борхардт вернулся в Германию, заявив своему еврейскому папе: «Кто-то же должен отстраивать нашу страну». В 1983 году, незадолго до смерти, Борхардт рассказывал немецким школьникам: «Многие евреи и полуевреи, воевавшие за Германию во Вторую мировую, считали, что они должны честно защищать свой фатерланд, служа в армии».

Но давайте вновь вернёмся к 150 тысячам евреев солдат и офицеров преданно служивших в вермахте Третьего рейха, «это 15 полнокровных стрелковых дивизий вермахта! – целая еврейская армада внутри вооруженных сил гитлеровцев» (16).

Арийским идеалом был боец вермахта еврей Вернер Гольдберг

[!] «Многие евреи и полуевреи, воевавшие за Германию во Вторую мировую, считали, что они должны честно защищать свой фатерланд, служа в армии».

рядовой вермахта Антон Майер

Кроме того, евреи воевали против СССР в составе стран-союзниц Третьего рейха во Второй мировой войне. Поход Гитлера на Россию носил общеевропейский характер (26).

Германия

К началу 1945 года в вооруженных силах Германии служило 9,4 млн. человек, из них 5,4 – в действующей армии. Кроме того, в составе войск СС числились чуть ли не полмиллиона граждан других стран, сведенных в национальные дивизии и более мелкие формирования. В них насчитывалось: выходцев из Средней Азии – 70 тысяч; азербайджанцев – 40 тысяч; северокавказцев – 30 тысяч; грузин – 25 тысяч; татар – 22 тысячи, армян – 20 тысяч; голландцев – 50 тысяч; казаков – 30 тысяч; латышей – 25 тысяч; фламандцев – 23 тысячи; украинцев — 22 тысячи; боснийцев – 20 тысяч; эстонцев – 15 тысяч; датчан – 11 тысяч; русских и белорусов – 10 тысяч (не считая 1-й дивизии РОА генерала Власова (16 тысяч человек), которая не входила в СС, полицейских и охранных батальонов и пр.); норвежцев – 7 тысяч; французов — 7 тысяч; албанцев – 5 тысяч; шведов – 4 тысячи.

Германия объявила СССР войну 22 июня 1941 года.

Венгрия

Эта страна была самым верным союзником Гитлера – вступила в войну 27 июня 1941 года и продолжала сражаться до 12 апреля 1945 года.

На советско-германском фронте в составе «Карпатской группы», 2-й венгерской армии и авиагруппы воевало до 205 тысяч мадьяров. Их силы увеличились до 150 тысяч на территории самой Венгрии. Общие потери – 300 тысяч человек.

Италия

В 1941 году режим Муссолини послал на советско-германский фронт 60-тысячный экспедиционный корпус в составе 3 дивизий. Позднее итальянские силы в России были доведены до 11 дивизий (374 тысячи человек), 2-й и 35-й итальянские корпуса стали непосредственной причиной поражения немцев под Сталинградом. В России погибли 94 тысячи итальянцев, еще 23 тысячи умерли в советском плену.

Италия объявила СССР войну 22 июня 1941 года.

Финляндия

Вступив в войну в конце июня 1941 года, Финляндия вернула себе почти все территории, отторгнутые у нее после «зимней войны». Финская армия (400 тысяч человек) дралась под Ленинградом, в Карелии, на Кольском полуострове. Потери составили 55 тысяч человек. После начала советского контрнаступления Финляндия вышла из войны, подписав в сентябре 1944 года соглашение о перемирии.

Испания

«Голубая» (250-я пехотная) дивизия воевала на советско-германском фронте с 1941 по 1943 годы. За это время на фронте успели побывать 40-50 тысяч испанцев. Дивизия воевала под Ленинградом и Новгородом (где испанцами был украден крест с храма Святой Софии). Потери: 5 тысяч убитых, более 8 тысяч раненых.

Румыния

Выставила против РККА 220 тысяч штыков и сабель, более 400 самолетов, 126 танков. Румыны воевали в Молдавии, на Украине, в Крыму, на Кубани, участвовали в оккупации Одессы, наступлении на Сталинград. В боях с Красной армией Румыния потеряла 350 тысяч солдат и еще 170 тысяч в боях с немцами и венграми после того, как в 1944 году перешла на сторону антигитлеровской коалиции.

Румыния объявила СССР войну 22 июня 1941 года.

Словакия

В числе стран – сателлитов Германии одной из первых объявила войну СССР – 23 июня 1941 года. На фронт были посланы 2 дивизии, которые сражались с Красной армией на Украине, Кавказе, в Крыму. Из 65 тысяч словацких военнослужащих с июля 1941 года по сентябрь 1944 года погибло менее 3 тысяч, в плен сдались более 27 тысяч солдат.

Хорватия

Прислала на помощь Гитлеру 369-й усиленный полк, моторизованную бригаду и истребительную эскадрилью общей численностью примерно 20 тысяч человек. Половина из них погибла или попала в плен под Сталинградом.

Норвегия

Сразу после 22 июня 1941 года в стране был объявлен набор добровольцев – ехать сражаться в Россию в составе германских войск. Уже в июле 1942 года под Ленинград прибыли первые подразделения эсэсовского легиона «Норвегия». Всего против СССР воевало 7 тысяч норвежцев.

Войну Норвегия нам объявила запоздало – 16 августа 1943 года (31).

А ещё были добровольцы – легионеры из Франции, Бельгии, Португалии и других стран, в числе которых были также евреи, добровольно вставшие на борьбу с христианской цивилизацией.

«Сколько погибло славян от рук евреев-эсэсовцев? Адольф Ротфельд, руководитель львовского юденрата, тоже сотрудничал с Гестапо. А офицер немецкой полиции безопасности того же Львова Макс Голигер, получил повышение по службе за свою изощренную жестокость. Еврейская полиция «Дистрикта Галиция» — «Юдише орднунг Лемберг» — «Еврейский порядок Львова» была сформирована из молодых и крепких евреев, бывших скаутов. Они носили форму полицаев с кокардами на фуражках, на которых было написано ЮОЛ, именно им, называющим себя «хаверами», эсесовцы поручали устраивать массовые истязания советских военнопленных в концлагерях и потом сами же удивлялись той жестокости, с которой молодые евреи относились к пленным солдатам. И это только один Львов…» (16).

«В крупнейшем Варшавском гетто еврейская полиция насчитывала около 2 500 членов в г. Лодзь — до 1 200; во Львове – до 500 человек, в Вильнюсе – 210, в Кракове – 150, в Ровно – 200 полицаев. Кроме территорий СССР и Польши еврейская полиция существовала лишь в Берлине, концлагере Дранси во Франции и концлагере Вестерброк в Голландии. В других концлагерях такой полиции не было» (18).

В варшавском гетто еврейская полиция имела специальный жетон с шестиконечной звездой.

«Если перечислять всех сионистских пособников нацизма, то список получится весьма длинным. Особенно если включить в него всех тех, кто через издававшиеся в еврейских гетто газетах призывал своих собратьев к покорности и сотрудничеству с нацистами, и тех, кто в составе так называемой еврейской полиции помогал нацистам отлавливать и депортировать в лагеря смерти десятки и сотни тысяч евреев» (30).

Сегодня «экс-арийцы дружно объявили себя евреями, сообща скорбят по жертвам холокоста, соучастниками которого они были сами. Они ругают фюрера и получают компенсации. Палачи объявили себя жертвами печальных обстоятельств» (16).

«Религия холокоста сконструирована теми людьми, которые сами несут главную ответственность за преследование евреев – сионистами! Это они привели к власти Гитлера, дали ему денег на большую войну и постоянно с ним сотрудничали…» (1).

Именно Гитлер субсидировал и направлял еврейский капитал на борьбу с СССР.

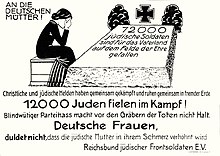

«Сотрудничество нацистов и сионистов было увековечено специальной медалью, отчеканенной по указанию Геббельса после пребывания руководителя еврейского отдела СС в Палестине. На одной стороне медали изображалась свастика, а на другой – шестиконечная звезда.

Гитлер запретил все еврейские организации и органы печати, но оставил «Сионистский союз Германии», преобразованный в «Имперский союз евреев Германии». Из всех еврейских газет продолжала выходить только сионистская «Юдише рундшау».

Выезжавшие под руководством сионистов из Германии в Палестину евреи вносили деньги на специальный счет в двух германских банках. На эти суммы в Палестину, а затем и в другие страны Ближнего и Среднего Востока экспортировались немецкие товары. Часть вырученных денег передавалась прибывшим в Палестину иммигрантам из Германии, а около 50 % присваивали нацисты.

Только за пять лет, с 1933 по 1938 год, сионисты перекачали в Палестину свыше 40 млн. долларов…

«По совокупности своих преступлений в годы Второй мировой войны, нацистские пособники из числа сионистов должны были оказаться на одной скамье подсудимых со своими патронами. Однако этого не произошло. Более того, те, кто прямо или косвенно сотрудничали с нацистами, оказались на высших руководящих постах как, например, тот же Вайцман или Леви Эшколь, в 30-е годы руководивший в берлинском отделении палестинского бюро депортацией немецких евреев в Палестину. Евреи рангом пониже заполняли средние и низшие звенья административной иерархии сионистского государства» (там же).

О масштабе участия евреев во Второй мировой войне против СССР убедительно свидетельствуют цифры военнопленных в СССР по национальному составу в период с 22.06.1941 года по 02.09.1945 года.

Из общего числа военнопленных 3 770 290 военнопленных (10, 26, 31):

|

Национальность |

Количество военнопленных, чел. |

|

немцы |

2 389 560 |

|

японцы |

639 635 |

|

венгры |

513 767 |

|

румыны |

187 367 |

|

австрийцы |

156 682 |

|

чехи и словаки |

69 977 |

|

поляки |

60 280 |

|

итальянцы |

48 957 |

|

французы |

23 136 |

|

югославы |

21 830 |

|

молдаване |

14 129 |

|

китайцы |

12 928 |

|

евреи |

10 173 |

|

корейцы |

7 785 |

|

голландцы |

4 729 |

|

монголы |

3 608 |

|

финны |

2 377 |

|

бельгийцы |

2 010 |

|

люксембуржцы |

652 |

|

датчане |

457 |

|

испанцы |

452 |

|

цыгане |

383 |

|

норвежцы |

101 |

|

шведы |

72 |

Из приведенной таблицы видно, что в плен попали 10 173 еврея – целая дивизия вермахта!

Хватало евреев и в плену войск антигитлеровской коалиции.

В условиях информационного общества замалчивание этих и подобных фактов явно бесперспективно.

Верными соратниками Гитлера по партии (НСДАП) и строительству вермахта были еврейские промышленники, действующие не только в Германии, но и во всей Европе и США. «Огромное количество вооружений производили чешские заводы «Шкода», французские «Рено» и др. Перед войной интенсивно наращивали военное производство американские заводы в Германии «General Motors», «Ford», «IBM» (37).

Вильгельм Мессершмидт (Messerschmitt), (1898-1978) – немецкий авиаконструктор, владелец десятков предприятий по производству самолетов для люфтваффе.

Фриц Тиссен (Thyssen), (1873-1951) – крупный немецкий промышленник, оказавший значительную финансовую поддержку Гитлеру, член НСДАП, щедро финансирующий её, активно способствовал приходу фашистов к власти.

Данный список бесконечно велик. Что стоит только один из его союзников по коалиции против СССР генерал Франсиско Франко, председатель правительства Испании, чистокровный еврей, обеспечивающий в годы войны сохранность богатых евреев Германии.

«Все войны всю человеческую историю организовывают еврейские оккультные силы, которые и внутри себя имеют два тайных ордена, которые борются между собой за власть. Евреи выработали основную тактику ведения войны – всегда орать, что евреев притесняют. И всегда получается, что ВСЕГДА ЕВРЕИ УБИВАЮТ ЕВРЕЕВ, а вину всегда евреи вешают на ни в чем не повинные народы» (16).

С 11 по 29 июля 2011 года в Женеве (Швейцарская Конфедерация) прошло 102 заседание Комитета ООН по правам человека, на котором для всех государств, подписавших Конвенцию по правам человека ООН (в том числе ФРГ, Франции, Австрии и Швейцарии), было принято следующее обязательное решение (замечание общего порядка):

«Законы, которые преследуют выражение мнения по отношению к историческим фактам, несовместимы с обязательствами, которые возлагает Конвенция на подписавшие ее государства относительно уважения свободы слова и свободы выражения мнения. Конвенция не разрешает никакого общего запрета на выражение ошибочного мнения или неправильной интерпретации событий прошлого» (Абзац 49, ССPR/C/GC/34).

Решение Комитета, как минимум означает, что уже действующие законы незаконны, и что они были противозаконными уже при их принятии, так что все проведенные за прошедшее время по ним осуждения должны быть отменены, а осужденные должны получить компенсацию.

Таким образом, для стран, подписавших Конвенцию по правам человека, преследование за отрицание холокоста является недопустимым.

Официальный текст решения (замечания общего порядка) Комитета ООН по правам человека на русском языке находится на сайте Комитета ООН по правам человека.

5 июля 2012 года Совет ООН по правам человека принял историческую резолюцию о свободе распространения информации в Интернете, в которой содержится призыв ко всем государствам защищать права личности в интернете в той же степени, в какой эти права защищаются в повседневной жизни.

«Совет по правам человека, руководствуясь Уставом Организации Объединенных Наций, вновь подтверждая, прав человека и основных свобод, закрепленных во Всеобщей декларации прав человека и соответствующих международных договоров по правам человека, включая Международный пакт о гражданских и политических правах и Международный пакт об экономических, социальных и культурных правах…

1. подтверждает, что те же права, что имеют люди, также должны быть защищены в Интернете, в частности, свободы слова, которое применимо независимо от государственных границ и любыми средствами по своему выбору, в соответствии со статьями 19 Всеобщей декларации прав человека и Международного пакта о гражданских и политических правах;

2. признает глобальный и открытый характер Интернета в качестве движущей силы в ускорение прогресса в направлении развития в его различных формах…

5. постановляет продолжить рассмотрение вопроса о поощрении, защите и осуществлению прав человека, включая право на свободу выражения мнения, в Интернете и в других технологиях, а также о том, как Интернет может стать важным инструментом для развития и осуществление прав человека, в соответствии со своей программой работы».

Отрицание холокоста – вполне законно!

Таким образом, исследование холокоста и его обсуждение есть дело науки, а не судьи по уголовным делам!

Источник: http://nets-buisnes.blogspot.ru/2014/02/blog-post.html

41

31859

The location of Germany (dark green) in the European Union (light green) |

| Total population |

|---|

| 116,000 to 225,000[1] |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Germany Israel, United States, Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and the United Kingdom |

| Languages |

| English, German, Russian, Hebrew, Yiddish, and others |

| Religion |

| Judaism, agnosticism, atheism, and others |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Ashkenazi Jews, Sephardi Jews, Mizrahi Jews, Israelis |

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321,[2][3] and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (circa 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jewish community. The community survived under Charlemagne, but suffered during the Crusades. Accusations of well poisoning during the Black Death (1346–53) led to mass slaughter of German Jews[4] and they fled in large numbers to Poland. The Jewish communities of the cities of Mainz, Speyer and Worms became the center of Jewish life during medieval times. «This was a golden age as area bishops protected the Jews resulting in increased trade and prosperity.»[5]

The First Crusade began an era of persecution of Jews in Germany.[6] Entire communities, like those of Trier, Worms, Mainz and Cologne, were slaughtered. The Hussite Wars became the signal for renewed persecution of Jews. The end of the 15th century was a period of religious hatred that ascribed to Jews all possible evils. With Napoleon’s fall in 1815, growing nationalism resulted in increasing repression. From August to October 1819, pogroms that came to be known as the Hep-Hep riots took place throughout Germany. During this time, many German states stripped Jews of their civil rights. As a result, many German Jews began to emigrate.

From the time of Moses Mendelssohn until the 20th century, the community gradually achieved emancipation, and then prospered.[7]

In January 1933, some 522,000 Jews lived in Germany. After the Nazis took power and implemented their antisemitic ideology and policies, the Jewish community was increasingly persecuted. About 60% (numbering around 304,000) emigrated during the first six years of the Nazi dictatorship. In 1933, persecution of the Jews became an official Nazi policy. In 1935 and 1936, the pace of antisemitic persecution increased. In 1936, Jews were banned from all professional jobs, effectively preventing them from participating in education, politics, higher education and industry. On 10 November 1938, the state police and Nazi paramilitary forces orchestrated the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht), in which the storefronts of Jewish shops and offices were smashed and vandalized, and many synagogues were destroyed by fire. Only roughly 214,000 Jews were left in Germany proper (1937 borders) on the eve of World War II.[8]

Beginning in late 1941, the remaining community was subjected to systematic deportations to ghettos and ultimately, to death camps in Eastern Europe.[8] In May 1943, Germany was declared judenrein (clean of Jews; also judenfrei: free of Jews).[8] By the end of the war, an estimated 160,000 to 180,000 German Jews had been killed by the Nazi regime and their collaborators.[8] A total of about six million European Jews were murdered under the direction of the Nazis, in the genocide that later came to be known as the Holocaust.

After the war, the Jewish community in Germany started to slowly grow again. Beginning around 1990, a spurt of growth was fueled by immigration from the former Soviet Union, so that at the turn of the 21st century, Germany had the only growing Jewish community in Europe,[9] and the majority of German Jews were Russian-speaking. By 2018, the Jewish population of Germany had leveled off at 116,000, not including non-Jewish members of households; the total estimated enlarged population of Jews living in Germany, including non-Jewish household members, was close to 225,000.[1]

By German law, denial of the Holocaust or that six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust (§ 130 StGB) is a criminal act; violations can be punished with up to five years of prison.[10] In 2006, on the occasion of the World Cup held in Germany, the then-Interior Minister of Germany Wolfgang Schäuble, urged vigilance against far-right extremism, saying: «We will not tolerate any form of extremism, xenophobia, or antisemitism.»[11] In spite of Germany’s measures against these groups and antisemites, a number of incidents have occurred in recent years.

From Rome to the Crusades[edit]

Jewish migration from Roman Italy is considered the most likely source of the first Jews on German territory. While the date of the first settlement of Jews in the regions which the Romans called Germania Superior, Germania Inferior, and Magna Germania is not known, the first authentic document relating to a large and well-organized Jewish community in these regions dates from 321[12][13][14][15] and refers to Cologne on the Rhine[16][17][18] (Jewish immigrants began settling in Rome itself as early as 139 BC[19]). It indicates that the legal status of the Jews there was the same as elsewhere in the Roman Empire. They enjoyed some civil liberties, but were restricted regarding the dissemination of their culture, the keeping of non-Jewish slaves, and the holding of office under the government.

Jews were otherwise free to follow any occupation open to indigenous Germans and were engaged in agriculture, trade, industry, and gradually money-lending. These conditions at first continued in the subsequently established Germanic kingdoms under the Burgundians and Franks, for ecclesiasticism took root slowly. The Merovingian rulers who succeeded to the Burgundian empire were devoid of fanaticism and gave scant support to the efforts of the Church to restrict the civic and social status of the Jews.